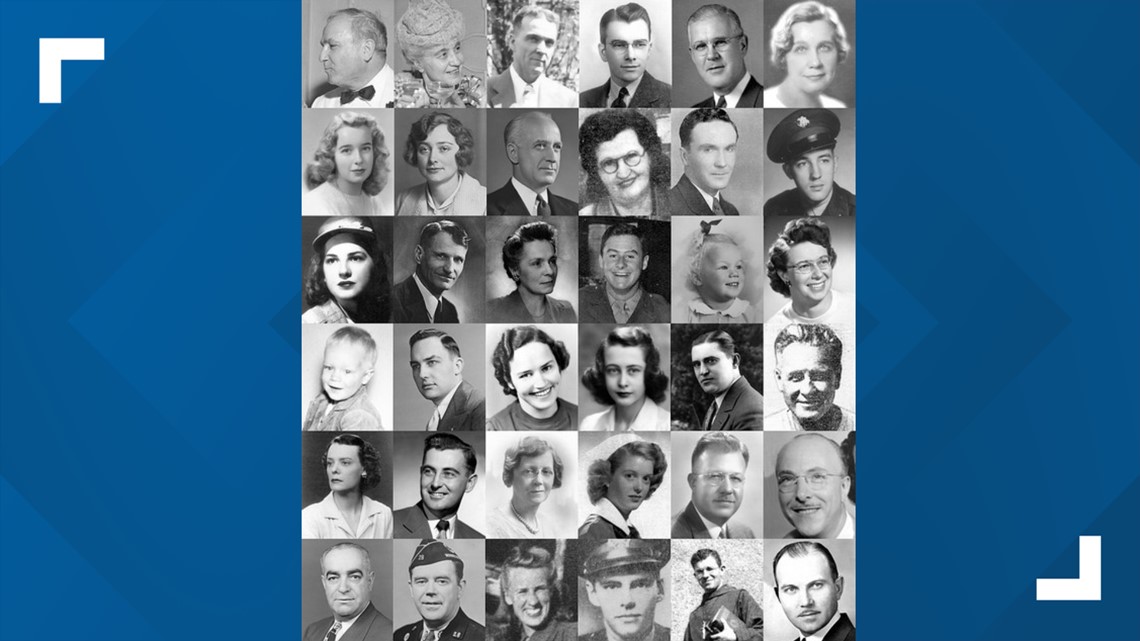

HOLLAND, Mich. — On June 23, 1950, Northwest Orient Flight 2501 was traveling from New York to Minneapolis. During it's flight path, it encountered a severe storm over Lake Michigan and mysteriously crashed, taking with it all 58 souls on board.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the tragedy, which, at the time, was the worst commercial air disaster in United States history.

Despite 16 consecutive years of exploration done by members of the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association, no pieces of the plane have ever been found.

That could change this summer.

Explorer and award-winning author Valerie van Heest, whose research determined definitively that weather caused the plane to crash, thought maybe weather could also be used to help her group solve the mystery of where the final resting place of the wreckage is located.

"We know this was a weather-related incident," said van Heest, co-director of the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association and author of the book Fatal Crossing. "June storms were quite prevalent then and they still are today."

Along with her team of researchers and divers, van Heest started searching for the remains of Flight 2501 in 2004. Every summer, weather permitting, they have spent countless days scanning the lake's bottom hoping to find a piece of the plane, which would serve as a symbol of closure for many of the surviving relatives of the victims.

"No intact human bodies were ever recovered," said van Heest. "A few personal items from some of the passengers were found floating on the lake's surface.

"We're grateful we've been able to provide family members with what caused the crash, but I also know how much finding some of the wreckage would be that final bit of closure."

In 2019, van Heest contacted the National Weather Service in Grand Rapids, seeking assistance. She explained to them about her ongoing search for 2501 and thought maybe having a better idea of what the storms truly did on that fateful night might help her find new areas to look.

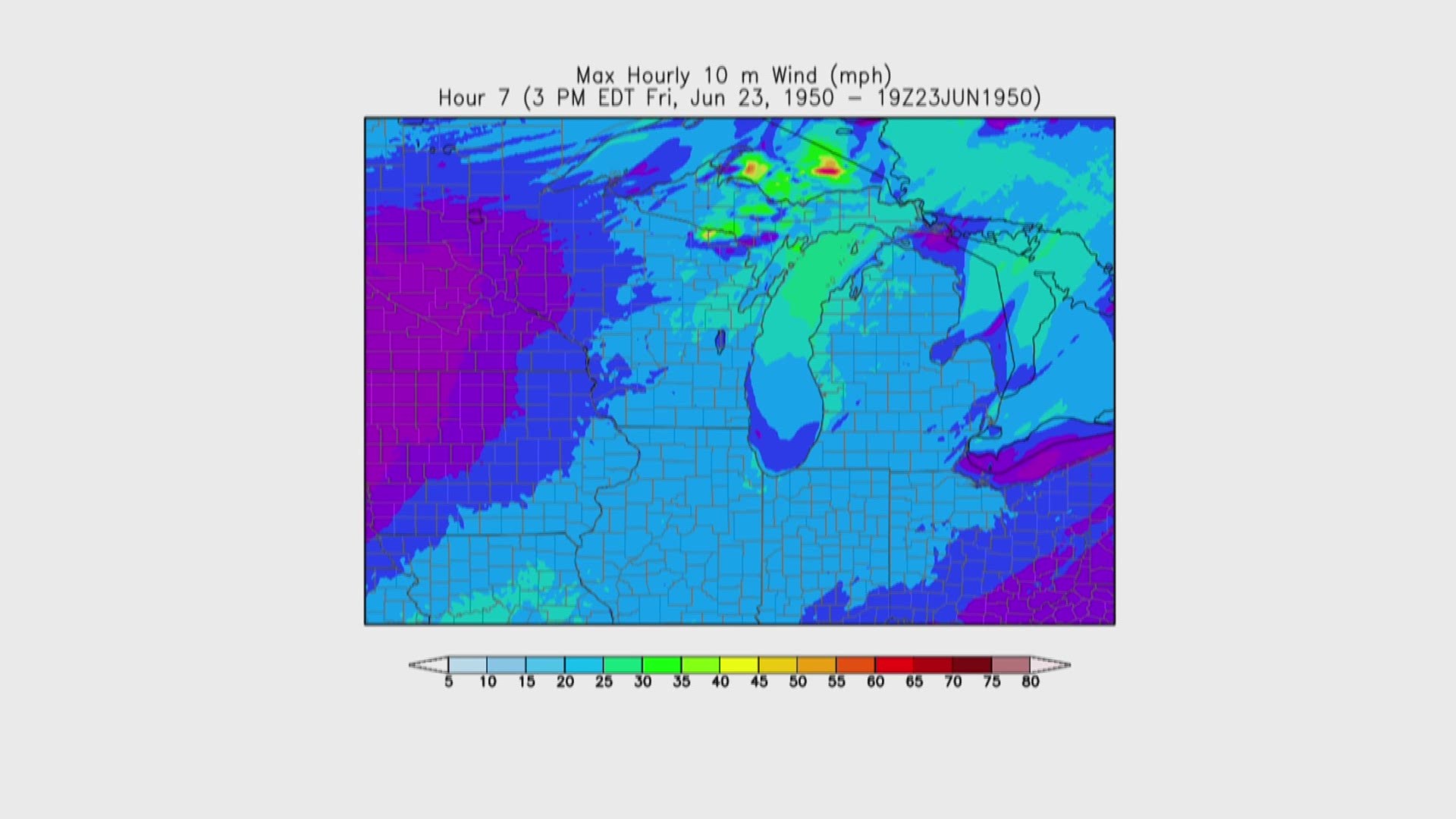

"After [Valerie] contacted us, we created something called a hindcast," said T.J. Turnage, who is the Science and Operations officer at the National Weather Service."We were able to pull up the storm data from June 23, 1950, from our archives, then run a computer simulation of what the weather most likely would have been during that event."

Turnage and his team of meteorologists created modern-day, real-time radar imagery of the storm, showing how it formed and where it intensified over the lake.

"It's kind of a way to plan back an event with your best guess of what happened," said Turnage. "Usually, with storms crossing Lake Michigan, they're moving to the east or to the southeast. This one started moving southeast, then due south and with increasing speed."

Turnage says this weatherman's version of instant replay can't simulate exactly how the storms looked on June 23, 1950, and what was exactly encountered by the airliner, but he adds it's as close as one can get, mixing 70-year-old data with today's technological advances.

Knowing how the atmosphere was acting above the lake's surface that night, Valerie also wanted to learn what may have been happening on the lake's surface, too.

"Search and recovery crews didn't start finding debris from Flight 2501 until 48 hours after the crash," said van Heest. "That means what they found had drifted for two days to move from the spot on the lake where the plane went down."

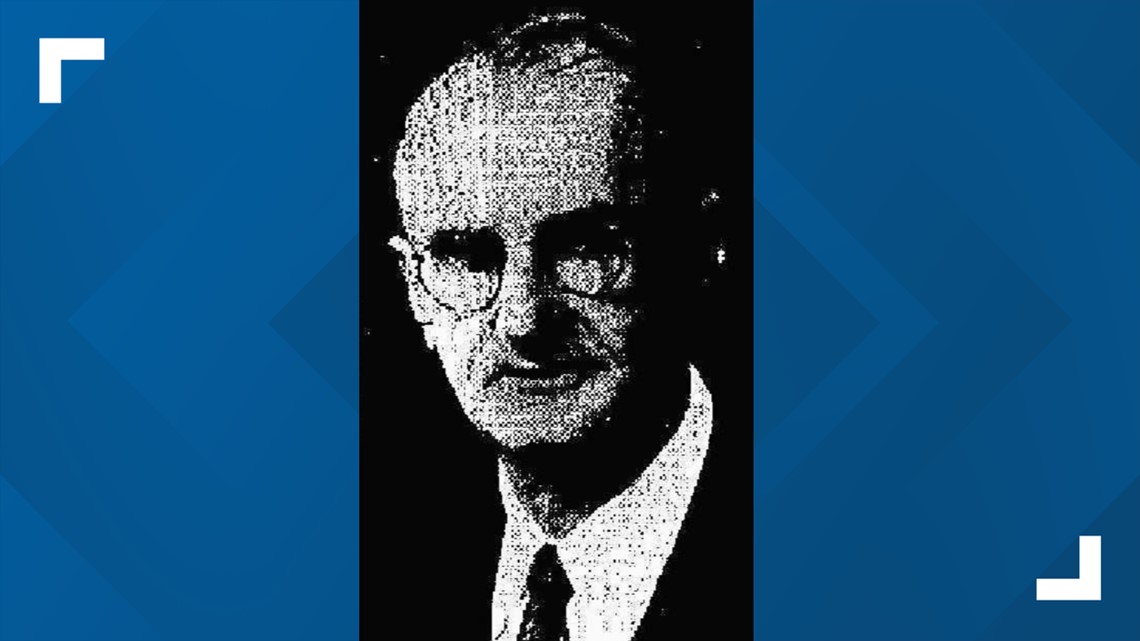

She researched and found Michigan native Dr. David Schwab, a retired scientist who spent 37 years with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Schwab's expertise is in predicting changes in the environment (wind, waves and current) on the Great Lakes.

"I study the interaction of physics of the Great Lakes with the atmosphere over the Great Lakes," said Dr. Schwab, who resides in Ann Arbor. "My job was to help guess where the plane might have gone down based on where the debris was found."

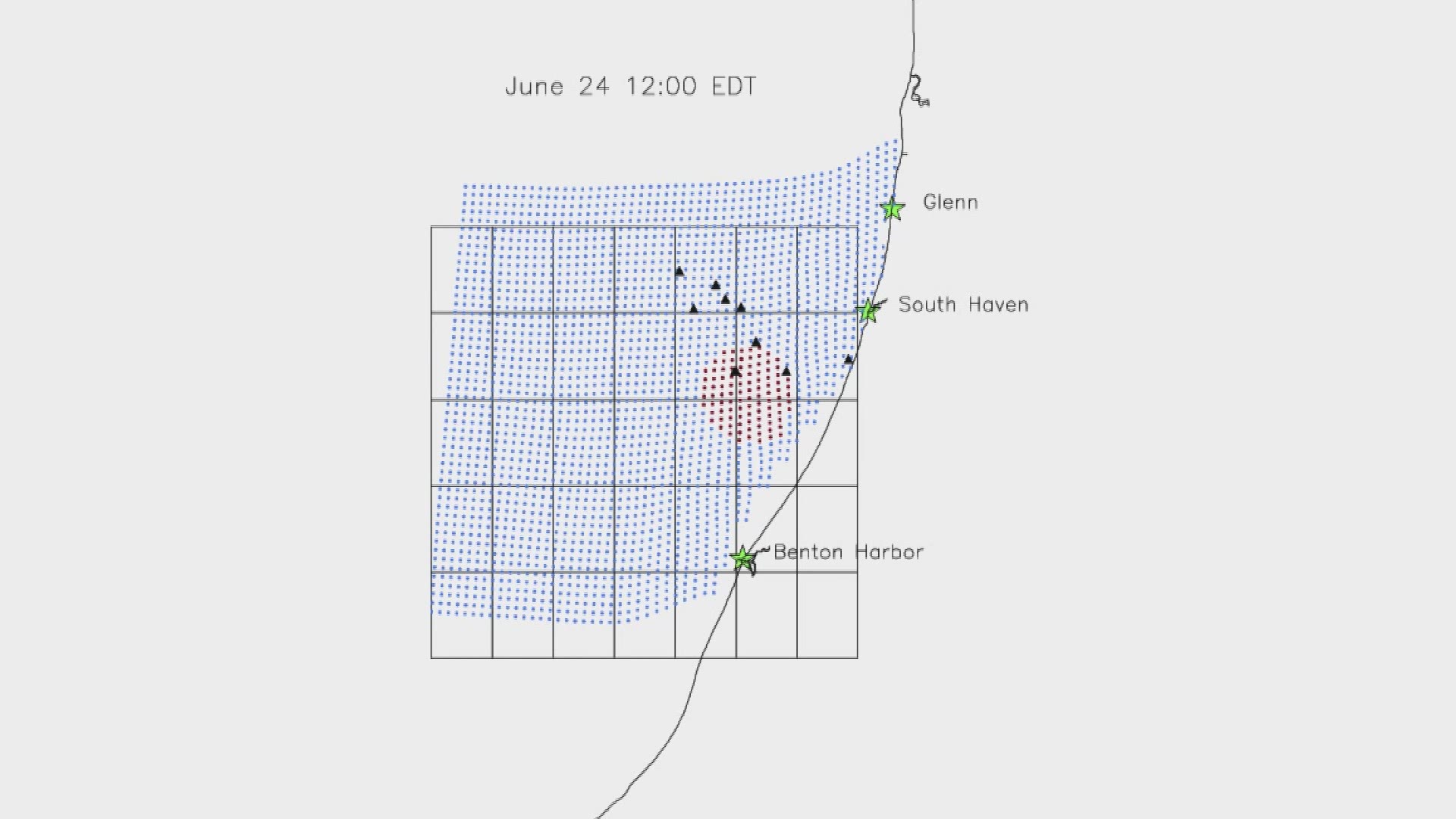

Dr. Schwab created a computer simulation of what the currents would have been like on the surface of Lake Michigan during the few days after the plane crashed.

"Based on those currents, and the winds over the lake, we can simulate how a piece of debris would move and where it would go hour by hour after it had started at some location," said Dr. Schwab. "I got meteorological date from the weather stations at Muskegon, South Bend, Chicago and Milwaukee, and interpolated those winds over the lake.

"We get a good estimation of what kind of wind was prevalent during that period when the plane went down."

Dr. Schwab also says that based on those winds, he can also use the models he created to estimate the currents in the water.

"Currents don't always go in the same direction as the wind," added Dr. Schwab. "If something's floating real high in the water, it's more affected by the wind than the current."

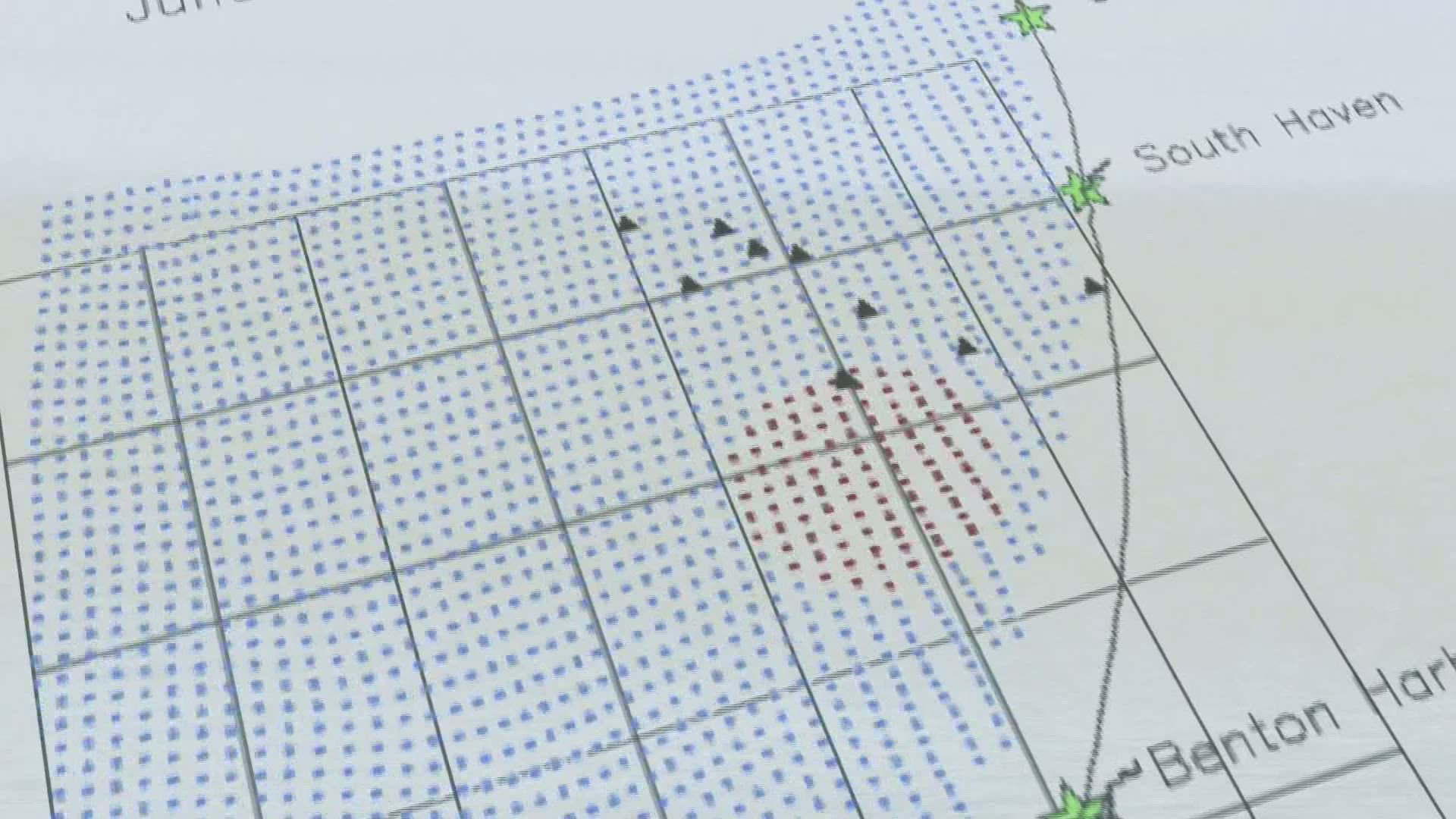

Each little red dot in Dr. Schwab's simulation represents a piece if debris.

"They're laid out in a grid like little bobbers," said Dr. Schwab. "All of the pieces of debris were released at the same time, which was around midnight when reports came in that the plane crashed.

"We tried to find the pieces of debris whose trajectory took them closest to the places and times debris was sighted by the rescue teams.

"Based on the correlation of the paths of these pieces of debris, with the location and times where actual debris was found, we can take the pieces of debris that came closest and look where they started, offering us a probability map of where the plan might have gone down."

Once van Heest checked out Dr. Schwab's simulation, she realized it revealed a spot on the lake where she and her team of explorers had not yet searched.

"His prediction caused us to become very focused on that area," said van Heest.

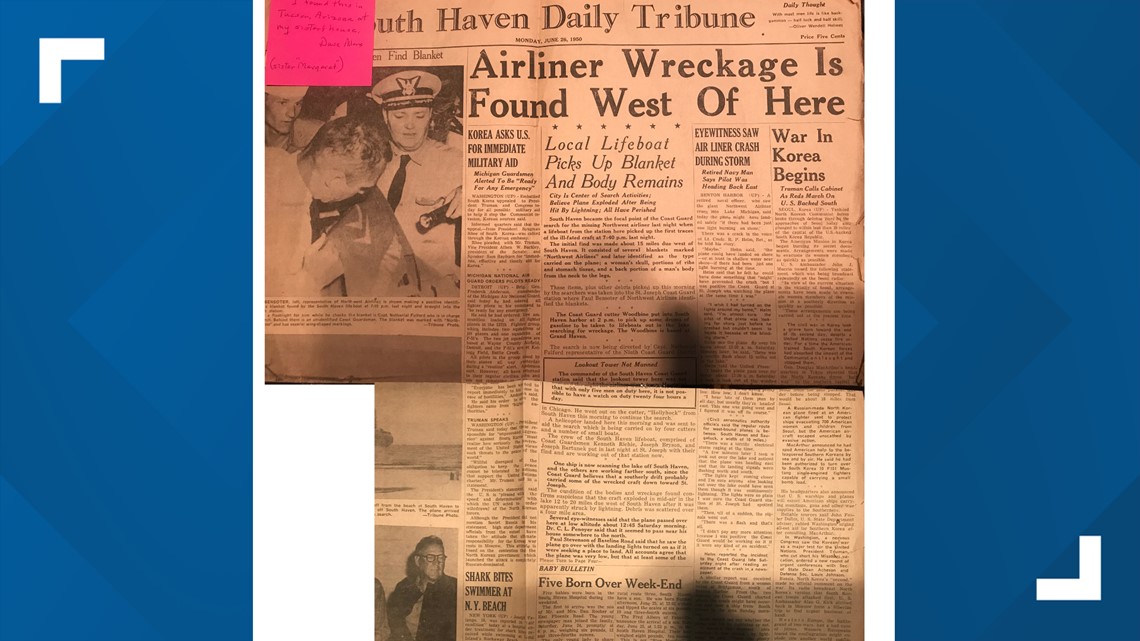

One week after van Heest collected and presented these two helpful weather simulations to her team, serendipitously she acquired an old issue of the South Haven Daily Tribune printed on June 26, 1950 — three days after the crash.

"In the newspaper, there's an article containing an eyewitness account of the crash," said van Heest. "I had never seen this account before."

The story is about a man named Raymond Palmer Helm, who happened to be outside his home near Benton Harbor watching the storm roll in that night.

Mr. Helm was quoted in the article saying, "There was a terrific electrical storm raging at the time. A few minutes later, I looked out over the lake, I noticed a plane was heading east and that its landing signals were flashing. The lights kept coming closer to my house."

After reading that particular quote, van Heest says she had to pause. All of her research she's ever done on Flight 2501 had the airliner heading west over Lake Michigan, likely intersecting with the storm, then meeting its fate.

"Not only did Helm see the plane that night, but he saw it turn around and come back to shore," said van Heest. "We have three studies [National Weather Service hindcast, Dr. David Schwab's debris simulation and R.P. Helm's account], that are all coalescing and pointing us to one spot on Lake Michigan to search."

Nothing controls Mother Nature except Mother Nature herself, but thanks to modern-day technology creating the ability to turn back time, maybe the weather can actually help Valerie van Heest and her group of explorers discover what it so savagely took 70 years ago.

"Now we're down to a very small search area and we're covering that this year," said van Heest. "We've got another shot at finding this."

When weather has allowed, members of the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association have been out on the lake scanning the new area

Expeditions began in late May and are stretching through June.

Their work is tedious, requiring long days on the lake, but van Heest and her group of explorers hope these new findings serve as the map to the wreckage, which has been resting somewhere in the deep for 70 years.

More from 13 ON YOUR SIDE:

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the 13 ON YOUR SIDE app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@13onyourside.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter. Subscribe to our YouTube channel.