In June of 1999, Dawn Brenner told her supervisor at Wolverine Worldwide’s tannery that water from the drinking fountain was changing colors.

“I was told, ‘There’s nothing that’s wrong with the water, Dawn,’” Brenner said. "'It’s coming straight out of the city. It’s not coming from here.’”

The water wasn't’ fine. It was being mixed directly with Scotchgard, the product Wolverine used to waterproof leather for its popular Hush Puppies shoes and other brands. The Scotchgard contained per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, called PFAS. The problematic chemicals leached from tannery sludge to contaminate hundreds of Kent County private wells.

Lavern Smith, who filled multiple jobs at the tannery from the late 1960's to when it closed in 2009, said the water turned rusty brown for a few days.

“I drank from the fountain one time, and I couldn't breath or anything,” Smith said. “I started getting nauseous, and I started turning blue.”

Multiple tannery employees said Wolverine brought them into the cafeteria and told them about the contamination. They provided bottled water.

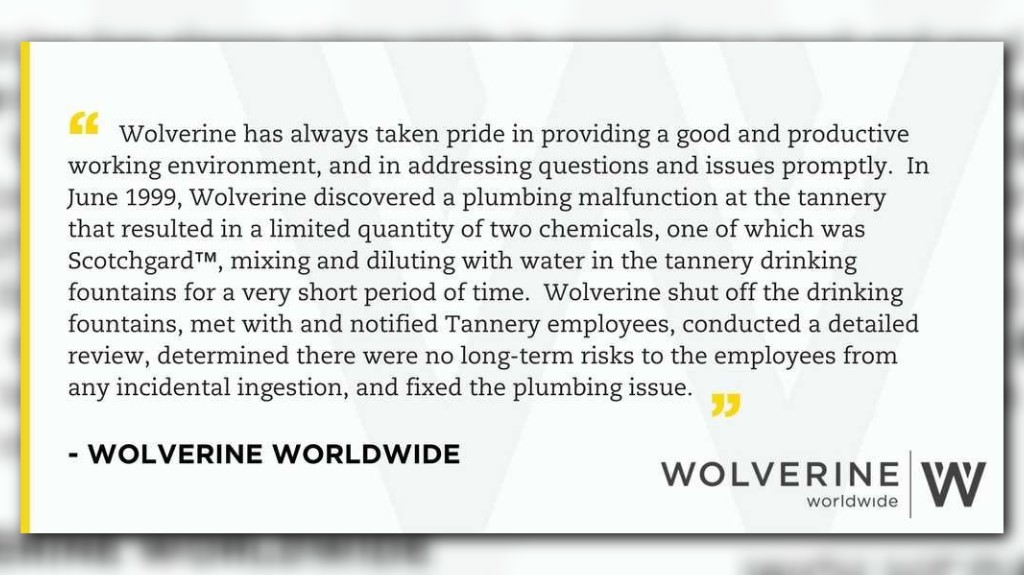

In a statement provided to WZZM 13, Wolverine Worldwide confirmed that two chemicals, Scotchgard and Anti-Stat 7493, “mix[ed] and dilute[ed] with water in the tannery drinking fountains for a very short period of time…[due to] a plumbing malfunction.” The company said it shut off the fountains, and “determined there were no long-term risks to the employees from any incidental ingestion.”

“They gave us the short term of what would be wrong,” Smith said. “You’d throw up, and you’d get dizzy and stuff like that. But they couldn't’ give us the long-term [consequences].”

WZZM 13 requested all complaints made to the Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration at the tannery through 2009. Even if the complaints existed, they are gone. The state deletes investigative records after five years.

Without MIOSHA records of the incident – duration and dosage – it’s difficult to assess how the chemicals might’ve affected those who ingested them, said Dr. Eden Wells, Chief Medical Executive at the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

It’s possible no one made a complaint about the contamination, said Cindy Koomen, who worked at tannery almost 34 years.

“Sometimes you think things are the way that they should be, especially when supervisors and people higher up, you know, are saying, ‘Oh, you know, it’s ok,’” Koomen said. “You believe that.”

Wolverine received a letter on Jan. 15, 1999 from 3M, Scotchgard’s manufacturer, warning the shoemaker about PFAS in the product. The letter mentions that some 3M workers occupationally exposed to the chemicals had PFAS in their blood at levels 100 times those exposed normally.

The letter reads, “PFOS has the potential to accumulate in the body with repeated exposures…[but] no adverse health effect associated with PFOS exposure has been found in 3M employees.” Wolverine would not say whether it contacted 3M after the incident. 3M could not find any related records.

There are links to some long-term illnesses and populations exposed to high levels of PFAS, Wells said.

“There has been an association…of potentially having risks of higher cholesterol [and] an effect on the liver function tests,” she said. “There may be an association with fertility issues…and certain cancers such as kidney cancer, testicular cancer and such.”

Wells cited a mid-2000s “C8” study conducted in the Ohio River Valley, called C8 because PFOA has eight carbons. In the study on nearly 70,000 people, investigators found elevated levels of PFAS in blood samples of the affected population with links to those illnesses.

In a November 2017 blog post, Wolverine downplayed the association, saying “human health effects from exposure to PFAS in the environment are unknown.” Dr. Janet Anderson, a consulting toxicologist for Wolverine, focused on the clinical inability to prove PFAS exposure “causes any illness.”

“We weren’t told about Scotchgard, PFAS, anything,” said David Avery, who worked at the Wolverine for 28 years. “We didn’t know what we was putting in there.”

3M phased PFOS and PFOA, the two PFAS chemicals most commonly found in the local groundwater contamination, out of Scotchgard production by 2002.

Both the federal government and the state of Michigan have safe drinking water advisory levels for PFOS and PFOA at 70 parts per trillion (ppt). Of the 1,500 wells tested since April, investigators have found more than 500 with detectable PFAS levels and 99 exceeding 70 ppt. One home in Algoma Township recorded 58,930 ppt of combined PFOS and PFOA.

Despite the overwhelming contamination, health officials have not called for a population-level blood study in northern Kent County. “A population approach to blood level testing is not indicated,” Wells said in November 2017.

Instead, the Kent County Health Department is working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to conduct a health survey for PFAS exposure. The survey was supposed to go out in the first few months of 2018, but is delayed indefinitely, according to KCHD.

“I’m just always going to have PFAS in my blood; it’s an inevitability now,” said Sandy Wynn-Stelt, who lives across from Wolverine’s old dump on House Street in Belmont. Her well came back with PFAS at 37,800 ppt, 540 times the EPA limit.

Varnum Law in Grand Rapids, a firm representing hundreds of clients in cases against Wolverine, paid for some people to get blood tests, including Wynn-Stelt. Her test detected PFAS at 5 million ppt, 3.2 million ppt of PFOS, more than 700 times the national average, according to a Red Cross study.

“It’s a little shocking when you see numbers that big,” Wynn-Stelt said in January. “It’s like I’m pretty much full of Scotchgard.”

That’s what the tannery employees want to know after the drinking Scotchgard-laced water and years of occupational exposure. It would make employees feel less like clock numbers if Wolverine considered their health effects, said Ray Bush, who got hired by the company in 1971.

“They should have a place where we can go just to go to your doctor and have them check you out,” Bush said. “If you need something that was caused from your work, they should be liable for it.”

Smith echoed Bush and said the shoemaker should test the tannery employees’ blood for PFAS and other contaminants. According to the CDC, individual blood tests for PFAS are not clinically predictive, but community testing for a study is most useful.

Some of the employees said their illnesses go hand in hand with those linked to PFAS. Wolverine needs to make things right with the people who were exposed every day, Koomen said.

“Now that this is all out in the open, the tannery workers should be considered as important as the residents [with contaminated wells],” she said

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the WZZM 13 app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@wzzm13.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter.