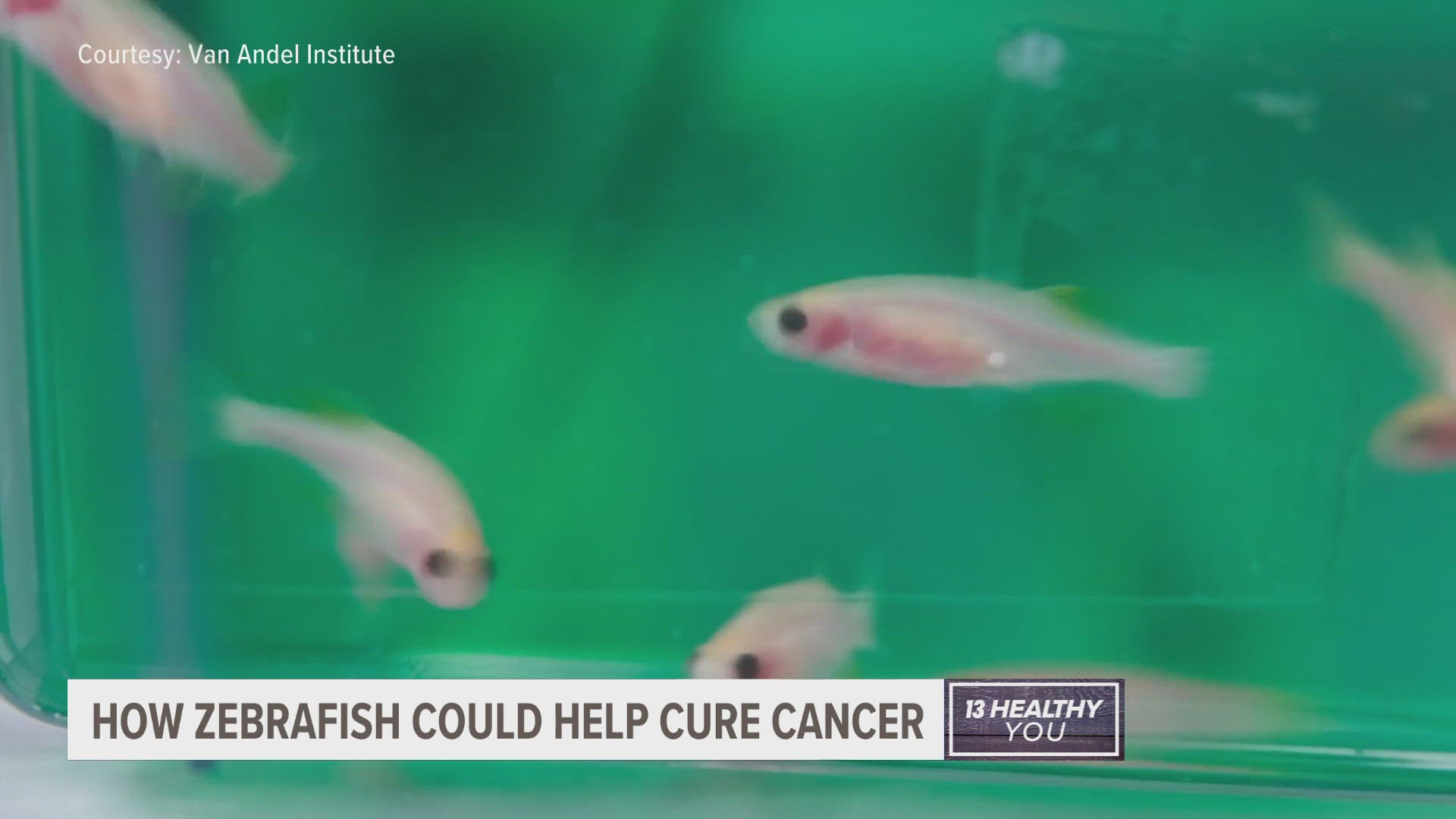

GRAND RAPIDS, Michigan — Huge cancer research is happening right in West Michigan. Scientists at the Van Andel Institute are using zebrafish to help develop stem cells for cancer research.

Dr. Stephanie Grainger said zebrafish are a great model to figure out how things happen during normal developmental biology.

Plus, they're see-through.

"So, we can actually see inside of the fish and see the cells as they're developing in real life," said Grainger.

Grainger and her team are trying to build stem cells in a dish. The goal is to find a better way to treat, or even cure, types of cancers without chemotherapy.

"If we can instead figure out how to make really specific drugs that target the specific genetics that go awry during cancer, then we'd be able to get around that toxicity of cancer therapies," said Grainger. "What we do is we study how particular genes behave in the fish, with the hope that we can then target those genes and cancer processes and make it a lot more specific."

Of course it is a lofty goal. Grainger said scientists have been working on making stem cells in a lab for more than 40 years.

"I feel like we're getting closer every day," said Grainger. "But it is a slow process."

The zebrafish also have multiple babies that grow outside the womb, making them easier to study than traditionally-used mice. Grainger said they have about 8,000 fish, which she says are living happy, health lives with lots of enrichment.

Specifically, Grainger said they are interested in a genetic signaling cascade called WNT. She explained it as the way cells talk to each other.

"What we were interested in is what happens when that WNT gets released and the other cell receives it," said Grainger. "One model is that that WNT that comes from the other cell just binds to a receptor on the outside. So, it's kind of like a lock and key mechanism, where you put your key into your front door, and they talk that way. But another model might be that rather than just the key going into the lock, and then talking that way, maybe the WNT actually opens the door and locks right in. What we've figured out is that in this very specific context, the WNT actually opens the door and walks right in. The cell has to eat the WNT for the signal to happen. Because that's sort of an unusual way of acting, it might be a good way to target cancers that have this signal that's happening, because it's not happening in all the cells of our body all the time."

RELATED VIDEO: 'I can do this.' Breast cancer patient encourages others on their journey

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the 13 ON YOUR SIDE app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@13onyourside.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter. Subscribe to our YouTube channel.