HOLLAND TOWNSHIP, Mich. - A pastor who’s experienced the torment of gang life firsthand is running a ministry to help troubled teens avoid the missteps that put him in jail and on the streets.

“I don’t want these kids to live the same life I did,” Pastor Willie Watt said.

The Chicago native started Escape Ministries, located on E 32nd Street, in 2008. Watt was born into a violent home to a prominent member of the Black Gangster Disciples.

After watching his friend get pushed in front of an oncoming train, Watt’s mother moved him and his sisters to Dowagiac. The abuse had already taken its toll.

“I was always violent; anger was my drug of choice,” Watt said. “I became evil like my father. I never trusted or loved anyone."

He moved to Holland years later, finding himself in jail in 2007 for threatening to kill his wife. Watt ended up homeless, sleeping in his car in front of Christ Memorial Church on Graaftschap Road.

“It’s a bit unusual, but, at the same time, that’s the way God works,” said Paul Scholten, an administrative pastor at Christ Memorial.

Church leadership gave Watt a part-time position working with some disadvantaged families in the community. That turned into mission work, but Watt knew he belonged back in Holland.

“There’s always a ministry for the very bad, you get that in jail,” Watt said. “There’s ministry for the very good, you get that in church. What about the kids that made mistakes or don’t know how to deal with trauma in their everyday life?”

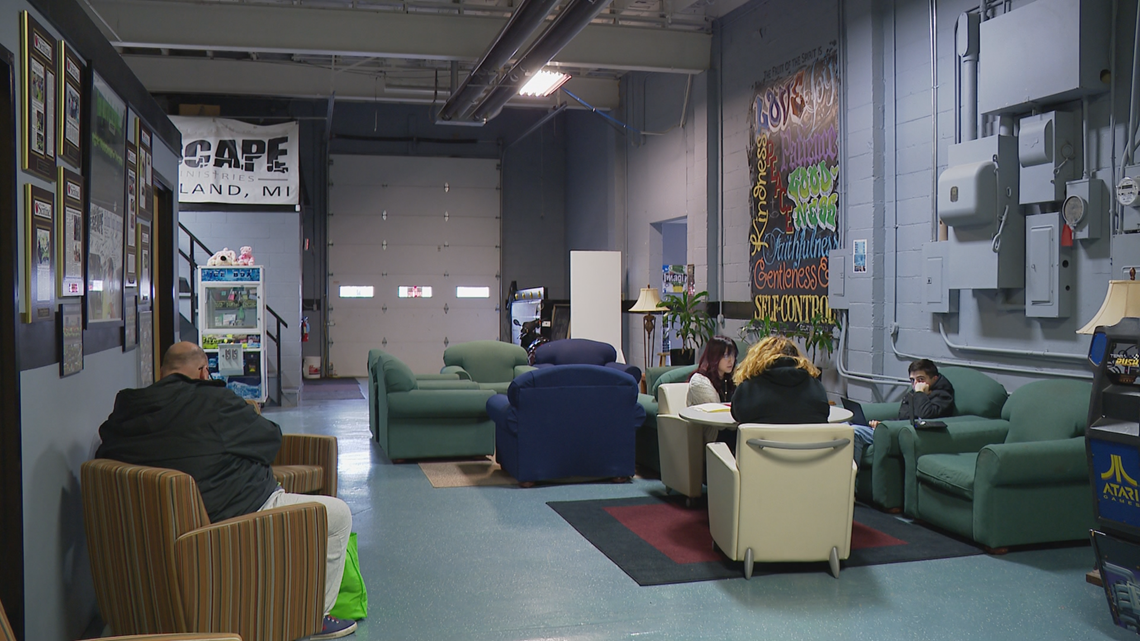

Escape takes in teens who otherwise might fall through the cracks, Program Director AJ Westendorp said.

“These are kids who are coming from difficult families, kids who aren’t used to being treated like they’re human beings with so much potential,” Westendorp said. “They aren’t having life spoken into them, but are still trying.”

'THE RIGHT DIRECTION'

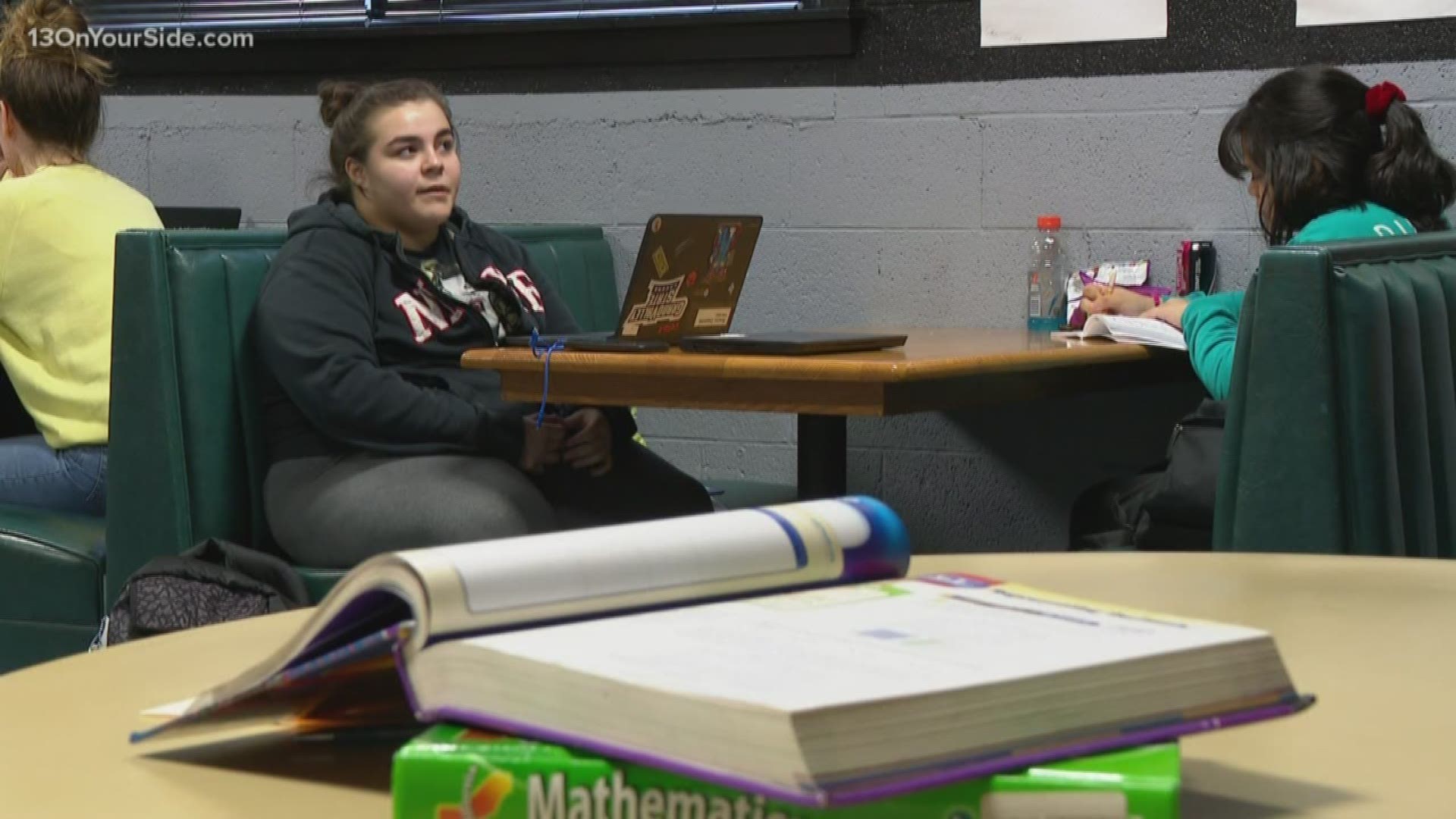

The ministry offers many services, including its Alternative Suspension Accountability Program (ASAP). It allows suspended or expelled students—disproportionately students of color—to continue their education and work towards returning to school.

ASAP recently received a social justice education award from the City of Holland’s human relations commission. The goal of ASAP is to interrupt the school-to-prison pipeline, Westendorp said.

“We see a lot of kids expelled from school, and they’re expected to then enter juvenile detention and end up in the prison system,” he said. “These kids are going to be in our society one way or another, and we prefer them to…be their best selves.”

The staff really cares to teach and help kids reach their goals, said 16-year-old Casandra Rincon.

“[My school] reviewed how well I was doing, and they let me go back to school before final exams,” Rincon said. “I made honor roll last semester.”

'GANG LIFE IS A LIE'

The students in ASAP want to return to school, but some have stronger motivators.

“My family was around gang life and violence,” said 15-year-old Aliyah Campos. “I thought I was going to be the first one to make it out like that and be something else.”

Holland is a beachfront, tourist community that still has a serious gang problem, Watt said.

“If you live under the surface of that, there is a whole different Holland that people don’t want to understand,” he said. “Now you don’t even have to join a gang to be in a gang. You can just say, ‘I’m down,’ and you’re inducted.”

Of nearly 2,100 kids that have come through Escape, more than 90 percent were gang-affiliated or knew someone in a gang, according to Watt. One student, Troy “TJ” Wells, was killed in a gang-related shooting in February of 2019. The ministry now has a music studio in his honor.

“The kid loved music and wanted to be a rap star, and I didn’t have a studio at the time,” Watt said. “What if I had one? I have so many success stories, but a lot of failures.

“If we’re not helping these kids with their dreams, their nightmares are going to take over – and that scares me.”

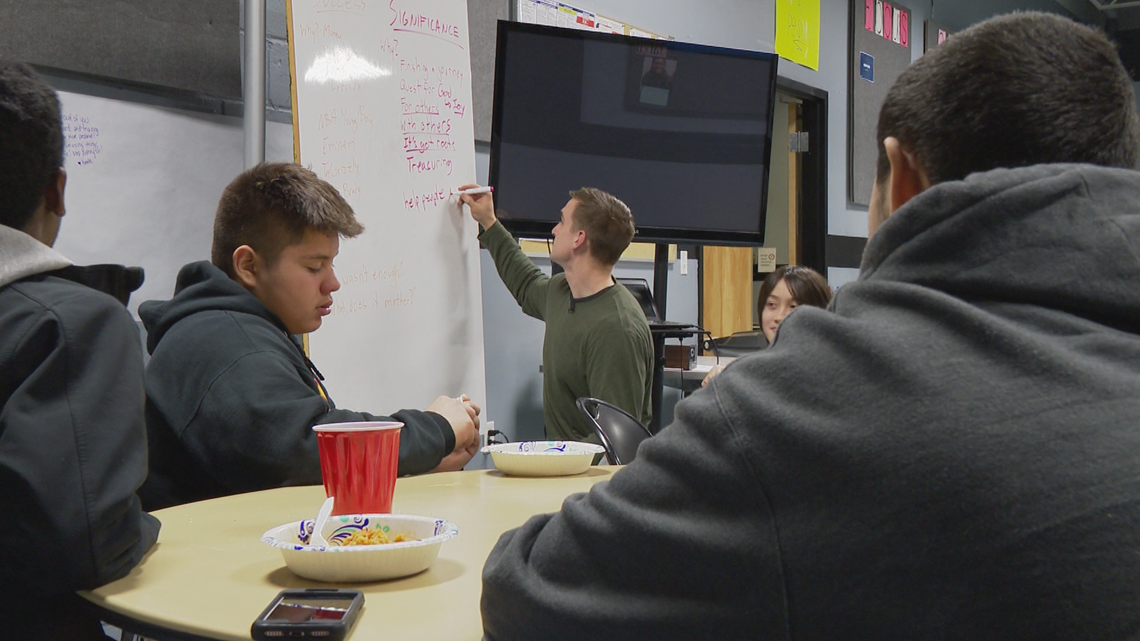

Many of these kids just need positive role models in their lives, Westendorp said. Each week, he hosts a roundtable dinner at the ministry called “Brotherhood.”

“We eat together; I think that’s a sacred time,” he said. “We talk about what it means to be a man. We create a community in which there are those young men to grow with, [and] it’s really valuable for them.”

These kids can change their paths today, Watt said.

“You don’t have to wait until you’re 40 years old like I did,” he said. “Everything I’ve done is to say, ‘Hey, I understand where you at and where you’re going, and I can help you get out of this.'”

There is nothing more rewarding than the moment a kid switches from being guarded and defensive into living fully as themselves, Westendorp said.

“We think slow relationships matter because trust develops slowly,” he said. “Sometimes it’s a success story, sometimes it means a slow, long struggle. But we’re here.”

Escape needs more funding, but what the area really needs is more organizations like it, Watt said.

“Just the kids alone we helped tell the story of Escape,” he said. “This is something everyone should be doing in their community.”

More stories on 13 ON YOUR SIDE:

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the 13 ON YOUR SIDE app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@13onyourside.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter. Subscribe to our YouTube channel.