MANISTEE, Mich. — Around the onset of the 20th Century, Arctic grayling went from being the most abundant fish in Michigan waters, to being completely gone.

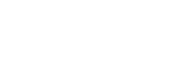

This cold water fish was mostly found in Michigan's northern, lower peninsula and served as the backbone of how the state's game and commercial fishing industry began.

What led to grayling's demise, and in the decades since, why has every restoration attempt failed?

A statewide collaboration, engineered by the Michigan's Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, has not only identified ways to bring grayling back, their momentum continues to build toward successful restoration of self-sustaining grayling populations so this native species can once again thrive in Michigan waters.

In the late 1800s, Arctic grayling were the dominant fish in Michigan's rivers and streams. They were multi-colored, almost iridescent, and sporting a long dorsal fin.

"They were very prolific," said Todd Grischke, DNR Fisheries assistant chief, and leader of Michigan's Arctic Grayling Initiative. "There were so many, you could walk on them across rivers."

Large populations of grayling flourished in both the Manistee and Au Sable Rivers. The fish was so important, a community within the state (Grayling, Mich.) adopted and bears its namesake.

Grayling's disappearance from Michigan can be traced to three main factors - each caused by humans: Habitat destruction, unregulated harvest and predation/competition with an introduced trout species.

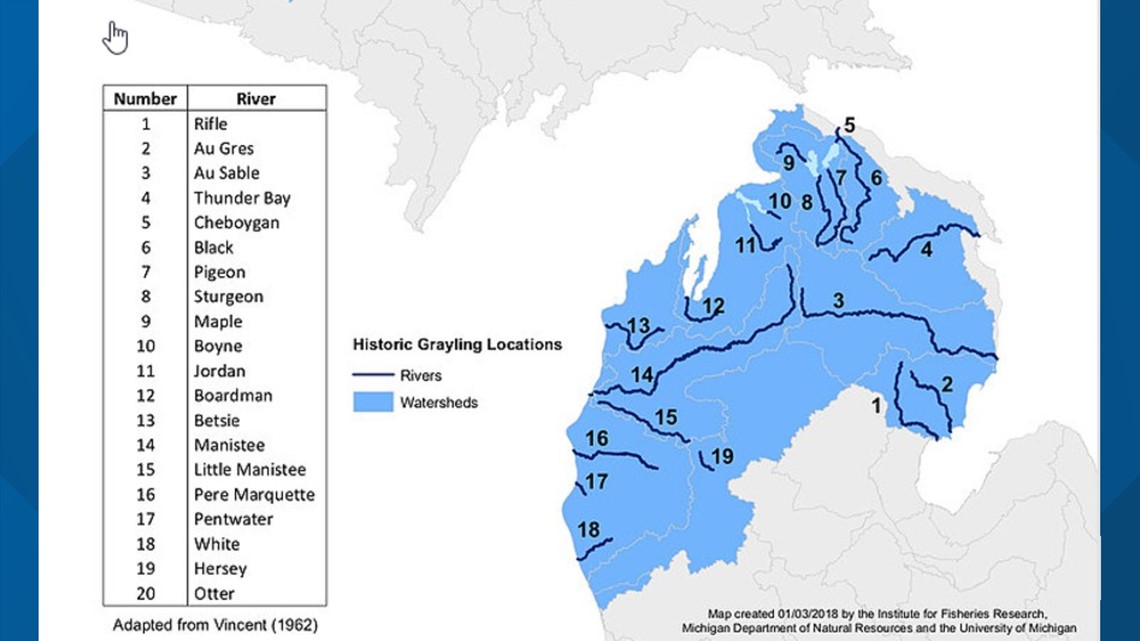

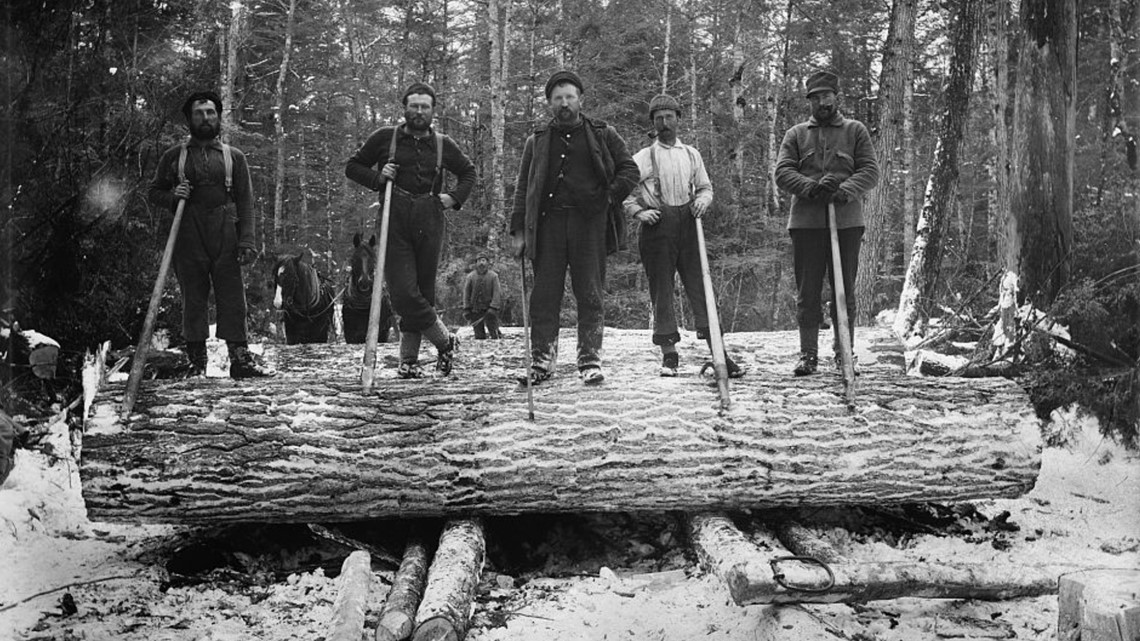

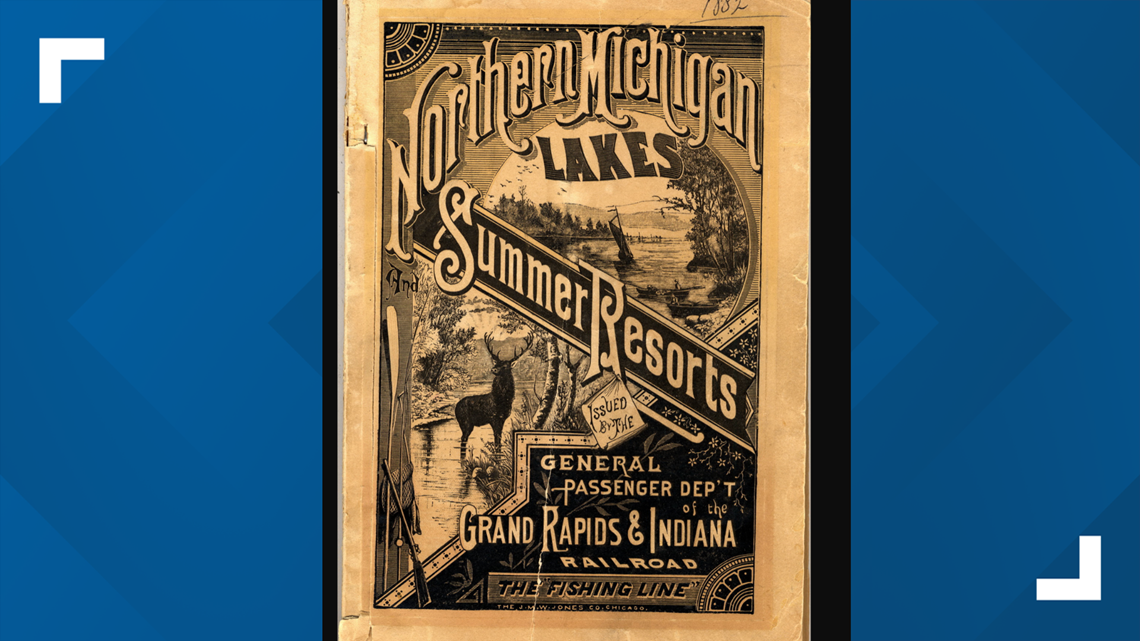

The turn of the century was when the lumbering era began in Michigan. Chicago needed to be rebuilt after the Great Fire, and the majority of the lumber used was taken from virgin forests along Lake Michigan's shoreline.

"Miles upon miles of White Pine was cut down," Grischke said. "The streams and rivers were used by loggers to float the massive pieces of timber to the sawmills.

"That process essentially wiped out the habitat of the native spawning fish that were there at the time, including grayling."

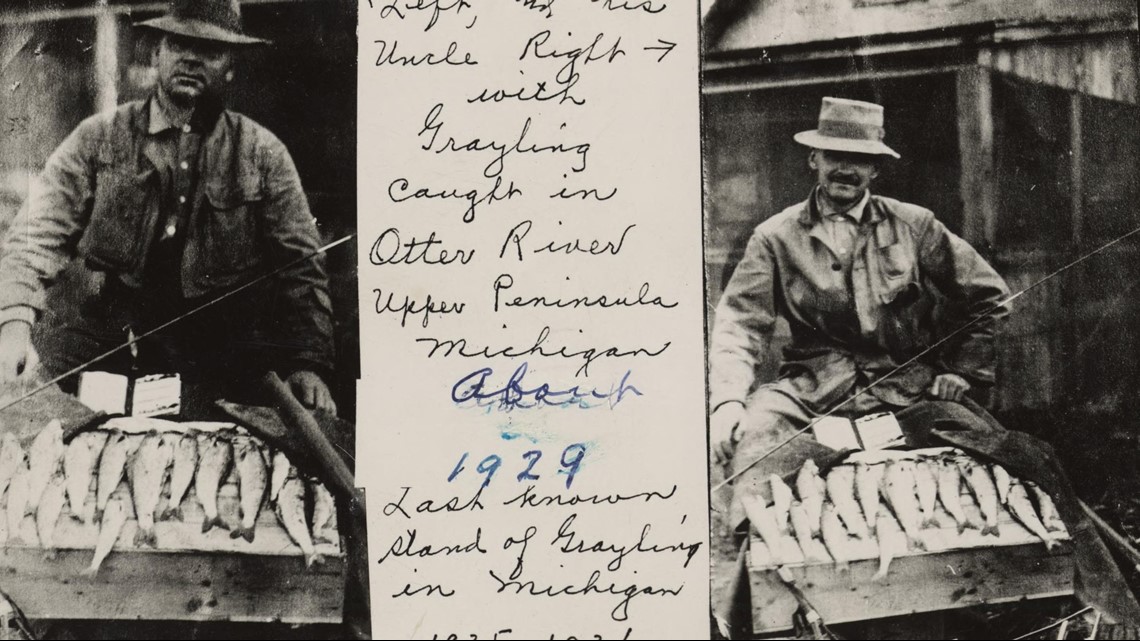

Simultaneously, big game fishermen traveled from far and wide to Michigan to catch grayling for commercial food use, further depleting the population of the species.

"There were stories of train cars being loaded with grayling and moved back to big cities like Detroit and Chicago," added Grischke. "There was no limit on how many grayling could be caught."

Lastly, brown trout were introduced to several Michigan waters and they would prey on grayling eggs.

"By 1930, the grayling population in Michigan was critically low," said Grischke. "Six years later, the demise of Michigan Arctic grayling was complete."

Grischke added that grayling weren't extinct; they were extirpated, meaning, "Grayling didn't exist in Michigan anymore, but they still did somewhere on Earth."

From the late 1930s through the late 1980s, there were many groups who attempted to reintroduce grayling to Michigan, but each one failed because the environment was no longer conducive to support grayling.

It would be nearly 30 years before the next legitimate attempt to restore Arctic grayling galvanized.

"Around 2013, there was interest by the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians in combination with some folks at Michigan Tech University," said Grischke. "We started doing assessments in the Upper Manistee River, where grayling were once supported."

That assessment, according to Grischke, was the springboard to drawing more statewide interest.

"In 2016, a partnership was formed between the DNR and Little River Band of Ottawa Indians," said Grischke. "Soon after that, more than 50 groups from around Michigan have also partnered."

Michigan's Arctic Grayling Initiative was born.

"It was just a perfect set of circumstances to collaborate," said Archie Martell, Fisheries Division Manager for the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians. "For the tribe, this is more about a cultural connection."

Along with providing funding for the Initiative, the tribe also offered centuries of valuable information and knowledge of grayling and what Michigan waters were truly like in the 1800s.

"The Manistee River runs directly through Little River's reservation," added Martell. "The tribe is historically connected to Arctic grayling."

Martell says the tribe has been engaged in extensive research for potential grayling reintroduction in Michigan long before the Grischke and the DNR identified them as a partner.

"The Upper Manistee River just seems like the best habitat that is directly connected to the tribe," Martell said. "Our efforts right now are focused on evaluating some of the tributaries to the Upper Manistee River to make sure they fit the criteria for a fish community."

Arctic grayling only existed in two of the lower 48 states: Michigan and Montana. Members of the tribe learned that advances and innovations in both scientific evaluation and fish culture techniques have allowed Montana to successfully carry out rehabilitation of grayling in a select number of their streams.

"We've made several trips to Montana to learn how they established self-sustaining populations of grayling there," said Martell. "Our goal is to follow what Montana has done and see if we can replicate that in Michigan."

Montana has been using in-stream units called Remote Site Incubators (RSIs), which are water supply systems built inside large buckets. Fertilized grayling eggs are placed on a tray inside the bucket, which is then put in the stream. The eggs incubate, then naturally hatch.

"They do what's called Imprint," said Martell. "They establish residency and know where to return and hopefully start building self-sustaining populations."

Martell says there's one issue that may prevent RSIs from working effectively in Michigan.

"Montana has higher gradient stream systems because they're in the mountains," said Martell. "Michigan has a lot of low gradient streams which have a lot of sand.

"The difference may be adapting the RSI technology that Montana developed and figuring out a way to re-engineer it to fit Michigan stream systems."

2021 marks the fifth year of Michigan's Arctic Grayling Initiative. While last year was nearly a complete loss due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the group still feels it's gaining momentum every day, but realizes restoring grayling to Michigan will be a marathon, not a sprint.

"To date, we have not reintroduced any grayling into Michigan streams," said Grischke. "We're still in the process of doing more habitat evaluations, and combing over quite a bit of information, especially about the Manistee River, which historically held the right temperature and the right flow."

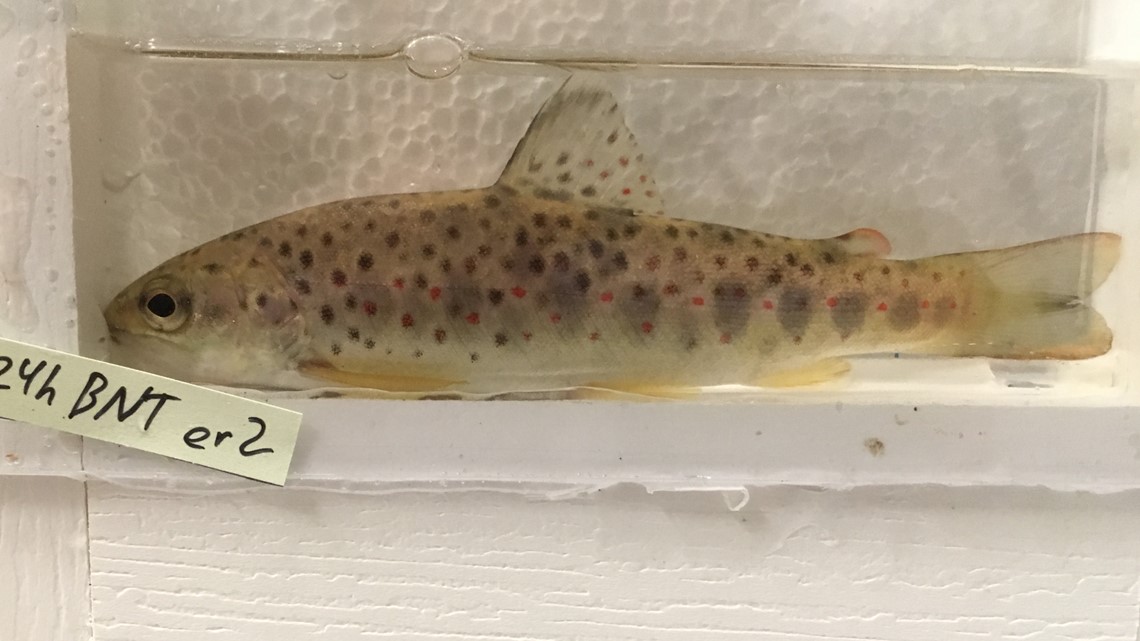

A critical part of the habitat evaluation continues today at Michigan State University where Artificial Stream Environment Trails are being conducted. Daniel Hayes, a professor in the MSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, and Nicole Watson, a doctoral student in Hayes’ laboratory, lead MSU’s portion of the project. They are interested in the ability of Arctic grayling to adapt to the new environments of select Michigan streams, and how those fish fare with respect to predation and competition with other fish species, like brook and brown trout.

In the two-month competition trials, each artificial stream holds 20 fish that are roughly 3 months old. The first contains all Arctic grayling, while the second is a mix of 10 Arctic grayling and 10 brook trout, and the third is a mix of 10 Arctic Grayling and 10 brown trout. Watson closely examines changes in growth, interactions and habitat use, with the hope of identifying a way all three fish species can co-exist in the wild.

Watson is finding that Arctic grayling are living harmoniously together and with brook trout. However, the brown trout are outcompeting Arctic grayling for food and habitat, but there's no significant predation happening. Watson indicated that these results match closely with those from similar studies in Montana.

Watson is also part of a team of scientists that travels to Fairbanks, Alaska, annually to procure fertilized Arctic grayling eggs to bring to Michigan for the establishment of a breeding population known as a broodstock.

"The broodstock fish will produce the first eggs that will be released into Michigan waters in roughly two to three years," said Grischke. "We are taking a methodical approach because this process can't be rushed."

Once the Arctic grayling mature, they're brought to the Marquette State Fish Hatchery where Grischke hopes they can create their own grayling eggs.

"We will continue to look at other state's successes, hoping to move closer to implementing the RSI in-stream incubators," added Grischke. "We're working hard to duplicate the success Montana is having and bring that to Michigan."

Grischke also adds that the Michigan Arctic graying Initiative is likely on a 10 to 15 year timeline, so it could be a decade before a self-sustaining population of grayling are once again thriving in Michigan rivers and streams.

"We're looking forward to that day when people will once again have an opportunity to catch Arctic grayling in Michigan," Grischke said. "It hasn't happened for almost a hundred years."

If you'd like to make a donation to help the efforts of the Michigan Arctic grayling Initiative, a direct link to the donation portal can be found here - Petoskey-Harbor Springs Area Community Foundation.

Related video:

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the 13 ON YOUR SIDE app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@13onyourside.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter. Subscribe to our YouTube channel.