NORTHPORT, Mich. — The Great Lakes have been sailed upon since the 17th century. Over the last 400 years, it's estimated that 6,000 vessels and 30,000 lives have been lost traversing these fresh waterways.

The most recent maritime tragedy was 44 years ago when the Edmund Fitzgerald found itself caught in a storm, ultimately sinking in Lake Superior on November 10, 1975, and killing the entire crew of 29.

Thousands of Great Lakes shipwrecks remain undiscovered, and many are lost forever.

A schooner that was recently found by happenstance in northern Lake Michigan. The find has provided closure to the 127-year-old mystery of what happened, and to a 93-year-old man who lost his great uncle when the vessel sank.

"On September 13, 2018, I was out with my cousins on Lake Michigan [boating] to North Manitou Island," said Ross Richardson, who is a shipwreck hunter known for his discovery of the Westmoreland in 2010. "I turned on my [side-scan] sonar so show them how it worked and within a couple minutes we ran over an interesting target."

After reviewing the images, Richardson said he knew he'd stumbled upon some type of sailing vessel, and based on his knowledge and research, he knew that there were a few missing in the area.

"It came 90 feet off the bottom which was extremely unusual for a shipwreck," added Richardson.

A few weeks later, knowing he was running out of quality weather days with fall coming, Richardson assembled a crew and went back to the wreck site to dive it.

This wreck is settled 300 feet deep, which is well beyond my range to dive it," said Richardson.

He contacted technical diver Steve Wimer II who is base out of from Milwaukee, Wisc.

"Whatever it was, I was going to be the first one to see it," said Wimer, who has been diving Great Lakes shipwrecks since 2005.

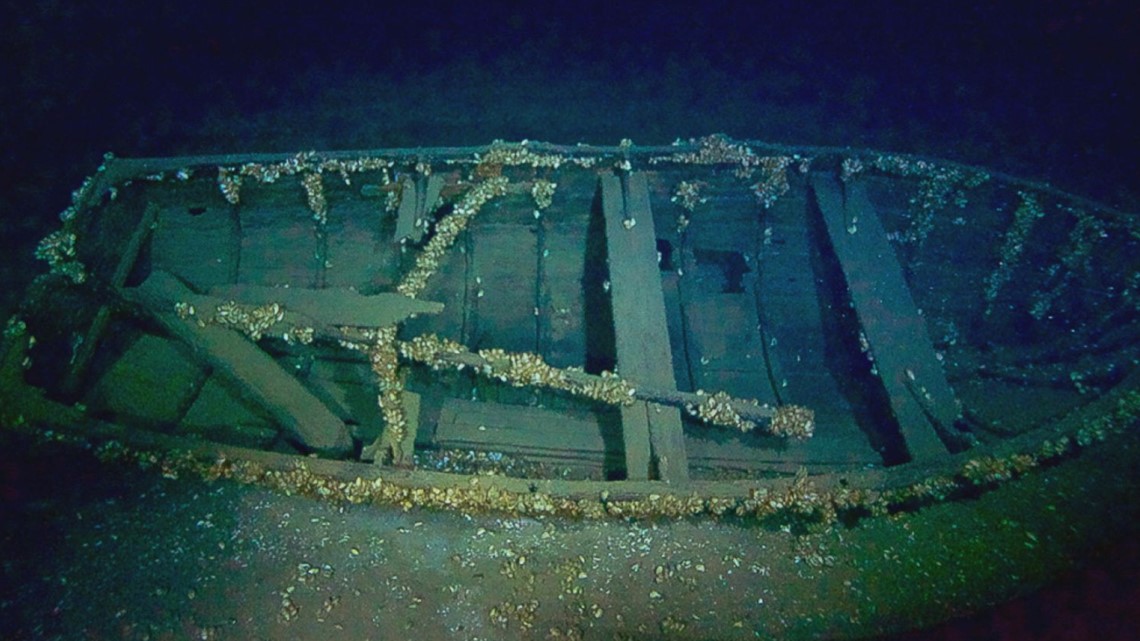

Wimer says as he descended, he could see the bow of a ship come into view. Once he reached the bottom, he was stunned by what was lying on the silt before him.

"It was a perfectly intact schooner," said Wimer. "Both masts were fully upright; all the rigging on the masts was there; the bowsprit was still there; the hatches are still battened down; the cabin is fully intact with the wheel.

"You could raise it, drain it, and sail away on it today."

As soon as Wimer resurfaced, he reported to Richardson what he saw.

"Steve felt the schooner was approximately 70 feet long," said Richardson. "We had other pieces to the puzzle to help us lead to an identification."

Fall would eventually give way to winter, preventing any more trips out to the wreck site for the remainder of 2018. His next shot at diving the wreck again would likely be in the spring of 2019, but that didn't prevent him from diving into something else - extensive research.

"I thought the wreck might be the Emily," said Richardson. "It fit the size and shape and disappeared in Lake Michigan in 1857."

The Emily was a 65-foot two-masted wooden schooner that was built in Milwaukee, Wisc. in 1853. It's believed the vessel foundered in a severe gale with a crew of six aboard.

All hands were lost.

"In late winter, I invited a friend over and I showed him the pictures of the schooner site and he spotted something," said Richardson. "He said the vessel had iron rope on it, and iron rope wasn't used on Great Lakes ships until after the Civil War.

"So, that eliminated it from being the wreck of the Emily because this unknown wreck had to sink post-1865."

Richardson was back to square one. He spent the winter and early spring months of 2019 scouring comprehensive databases of Great Lakes schooners, specifically ones that were presumed and known to be lost around the Manitou Islands.

"I read through over 6,000 records," said Richardson. "Of the 6,000, I was able to identify about a dozen that matched, but one of them really stood out - a schooner that seemingly disappeared off Point Betsie, which is 15 miles south of the wreck site."

The standout was the W.C. Kimball schooner, which sank in Lake Michigan in 1891.

"We were lucky enough to find an actual photograph of the W.C. Kimball, which gave us the rare opportunity to compare it to the underwater photos Steve [Wimer] took when we dove the wreck six months prior.

"We knew this would help with the identification process."

As the weather finally started to warm up, Richardson, Wimer and Kothrade decided to load up the boat and head back out to the site to do another dive.

"Spring is a perfect time to dive shipwrecks because that's when the visibility is the best," said Richardson. "Steve was able to take a few photos of the site during the first dive, but we needed video so we could cross-reference it with the photo of the Kimball."

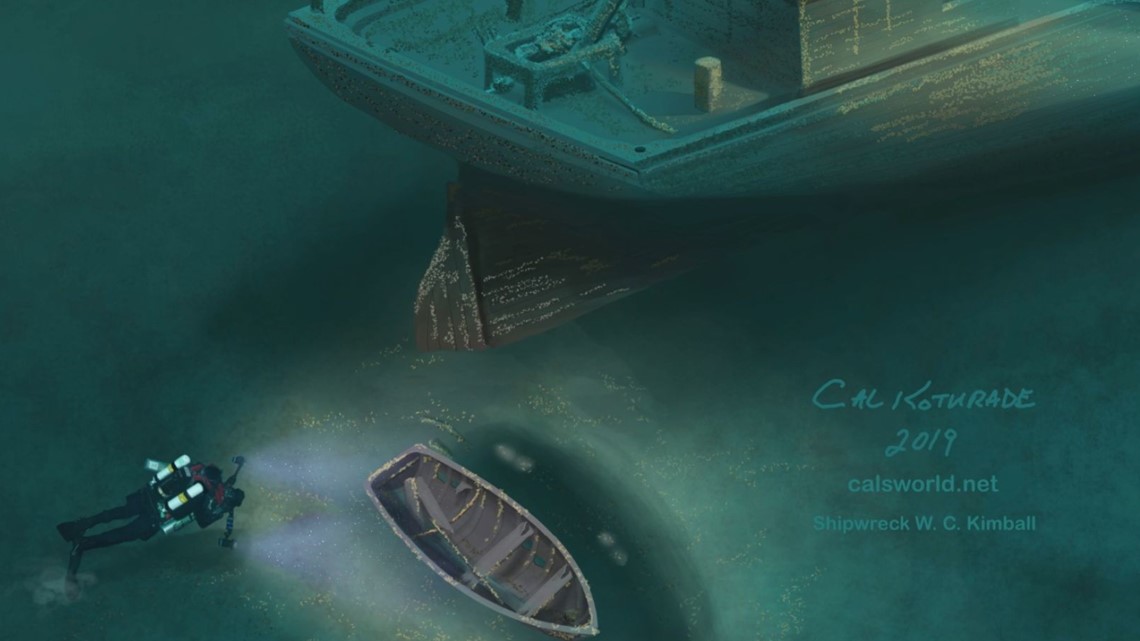

During this second dive, Wimer took an underwater video camera with him, with the intent of capturing footage of every angle of the wrecksite. Richardson added four more crew members - ROV (Remote Operated Vehicle) pilot Bryan Dort, Brent Tompkins, who served as support in the boat, maritime artist and diver Cal Kothrade and his father Roger Kothrade.

"Steve was able to video tape the wreck from bow to stern," said Richardson. "At this point we were all about 80 percent certain this was the W.C. Kimball."

While Wimer continued his dive, Richardson and Kothrade remained on the boat and watched a 40-inch monitor that was broadcasting a real-time video feed from the ROV camera.

"I was looking for what I believed to be the smoking gun," said Kothrade, whose digital maritime artwork helped play a huge role in identifying the wreck. "I looked at the photograph of the W.C. Kimball and was able to discern certain details that were very rare to ships of that time period.

"If we could find the running lights on the wreck, then I would know with certainty that we had found the Kimball."

Kothrade says he scoured both sources of footage (the video Wimer shot as well as the ROV material) and found what he was hoping to find.

"There it was," said Kothrade. "The running lights were there which allowed Ross to positively identify the wrecksite as the final resting place of the W.C. Kimball."

The W.C. Kimball was built and launched from Manitowoc, Wisc. in 1888. The schooner eventually started operating out of Northport, Mich., and often sailed along the coastline of Lake Michigan to Chicago and back, delivering salt, roofing shingles and potatoes at various ports of call.

Richardson says on the evening of May 7, 1891, the Kimball cleared the pierhead at Manistee and headed north towards her home in Northport. Early in the morning of May 8, a northwest gale arose and pummeled northern Lake Michigan.

The Kimball foundered and vanished.

A few days later, a vessel passed through a wreckage field off Point Betsie, just north of Frankfort. Shingles were spotted floating off North Manitou Island and began washing up at Cathead Point, at the tip of the Leelanau Peninsula.

Later that summer, a few personal items washed ashore near Leland, Mich. Charles Kehl's cap, Karl Andreason's trunk with letters inside and a small blue hatch cover.

The beaches between Frankfort and Northport were searched regularly, but the bodies of the Kimble tragedy were never recovered.

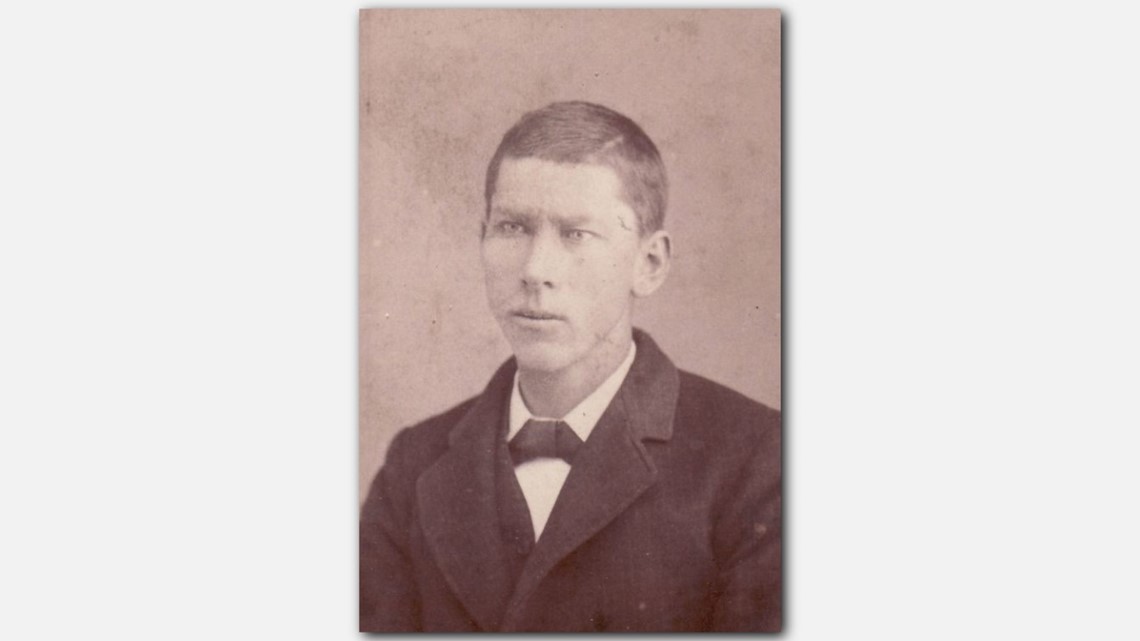

Five months after making the identification, Richardson, Wimer and Kothrade gathered in Northport and met with William G. Thomas, whose great uncle was Charles Kehl - one of the sailors who lost his life aboard the Kimball.

"They found my uncle's cap floating in the lake but that was all," said Thomas, 93, who was a former physician in Northport. "I've always been interested to know more about it because it's in the family history.

"It's a great thing to know finally know where he is."

Thomas had yet to see any photos or video of the site. That's when Cal Kothrade decided to pull up some images on his phone and show him.

"That's amazing," Thomas said, as he became the first member of his family to set eyes on Charles Kehl's final resting place. "You've got me excited now and I have high blood pressure!"

It was a moment of family closure that took 127 years to unfold. Thomas had to live 93 of those 127 years to become the beneficiary.

"It's terrific that they found it," said Thomas. "It's the thrill of of the day."

Richardson says even though he's positively identified it, he never plans to return to the W.C. Kimball site again.

"Those top masts are way too delicate," said Richardson. "In grappling that wreck, even though we used as little of an intrusive process as possible, there's still a chance you could cause damage.

"That thing will continue to be preserved in 39 degree water for hopefully another hundred years."

Crew lost aboard the W.C. Kimball:

* James Stevens - Captain

* Charles Kehl

* Karl Andreason

* William P. Wolfe

If you know of a story that should be featured on "Our Michigan Life," please send a detailed email to 13 ON YOUR SIDE's Brent Ashcroft at life@13onyourside.com.

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the 13 ON YOUR SIDE app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@13onyourside.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter. Subscribe to our YouTube channel.