The family of a Muslim Marine recruit from Taylor who died two years ago in a fall at boot camp at Parris Island, S.C., is raising new issues about his death, saying missing, inconsistent and mistake-ridden records have left them questioning again what really happened to Raheel Siddiqui.

Heading into a federal court hearing this Thursday in Detroit in a $100-million lawsuit they have filed against the Marine Corps, the family is now considering suing the local coroner in South Carolina who ruled the death a suicide, as well as paramedics, a medical transport company and two hospitals after being given records that the family doubts are authentic or accurate. Siddiqui died in a three-story fall from his barracks, reportedly after being hazed and slapped by his drill instructor.

Two weeks ago, the Free Press first reported that the family had been told that the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, where Siddiqui was reportedly transported and died on March 18, 2016, had no record of him. Since then, the hospital has located and sent the family just such a record, though the Siddiquis are still questioning its accuracy and why it couldn't be readily found in the first place.

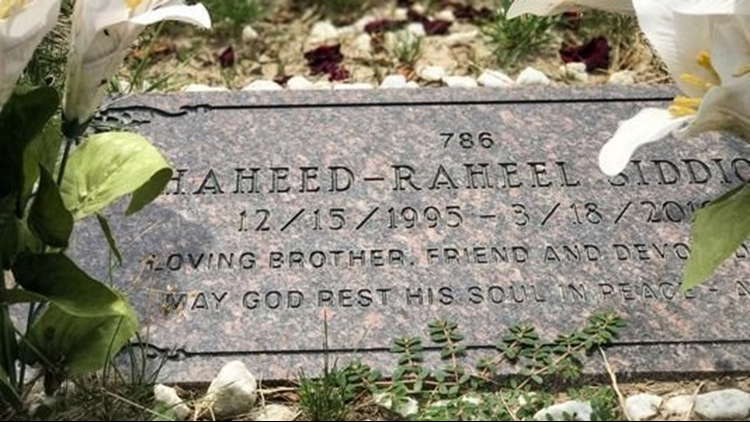

Raheel Siddiqui, 20, of Taylor, died during U.S. Marines boot camp training in South Carolina in March 2016. (Photo: Family photo)

But that is just one of myriad errors and inconsistencies the family says need to be explained in records shared with the Free Press. Among them:

- Why was Siddiqui first treated for 1½ hours at Beaufort Memorial Hospital — not far from Parris Island — when it apparently did not have a cardiovascular surgeon, before being transported to the MUSC, even though a helicopter arrived to take him there just three minutes after emergency medical technicians brought him to the local hospital?

- And how, as a nurse’s record said, could Siddiqui have denied, during a screening at 7:05 a.m., more than an hour after his fall, being subjected to “threats or abuse” or “injuries from another,” when medical assessments said he was brought in as “unresponsive” and “unconscious," having suffered a chest injury, fractured ribs and internal bleeding.

- Why did one form, regarding medications, have a line that appeared to the family to suggest that the patient was pregnant or breastfeeding and was a smaller and lighter person than Siddiqui?

- Were there questions about Siddiqui’s suitability to be moved to MUSC by helicopter at 8:06 a.m., after he was treated at Beaufort? A record from the transport company says, “ER MD relates that pt needs a CV surgeon, which they do not have at Beaufort … decision is made to transport even with pt’s unstable condition."

- And why does the medical examiner who performed an autopsy at MUSC on Siddiqui in one place say the time of death was 10:06 a.m. and, in another, 10:45 a.m., when the death certificate lists the time of death as when he fell, at 5:45 a.m.? Why was the autopsy report changed, a month after it was initially finalized, to say Siddiqui was identified by a misspelled toe tag that read "Siddioue," and not, as the initial report added, by MUSC and/or the local coroner?

“We know he died in South Carolina. We don’t really know anything else,” said Southfield attorney Shiraz Khan, who represents Siddiqui’s family. “The family believes they’ve been provided no evidence that corroborates the narrative (of his death).”

Even the report on Siddiqui's treatment and death sent by MUSC last week by mail raises doubts, the family said, saying they've found "questionable entries and unsubstantiated history" in the record," though Khan was not specific. Meanwhile, the family also wonders why it has received no information at all from local emergency medical technicians who, according to other reports, were the first ones who reported that Siddiqui had jumped over a third-story stairwell railing and that his injuries were — apparently — "self-inflicted."

Because of those errors, inconsistencies and missing records, Khan recently sent a notice of intent to sue to the local coroner, J. Edward Allen, as well as the hospitals, the transport company and the local emergency medical service, threatening claims of fraud, misrepresentation and other counts.

The family also wants Allen to change the cause of death from "suicide" to "undetermined" or "pending" as it has long argued for, saying not only that Siddiqui would not have killed himself but that Allen hasn't shown any conclusive evidence that the Marine recruit intended to commit suicide.

“If they have a witness, I’d love for them to bring this witness to me,” Khan said.

Two weeks ago, when asked about the discrepancy regarding the time of death, Allen acknowledged it could be a "typo" and that Siddiqui died at MUSC. Since the family sent a notice regarding the possible lawsuit, however, neither Allen nor the other potential parties — nor the Beaufort County attorney, Thomas J. Keaveny II — would talk about the possible lawsuit or the records already in the family's possession.

Some facts known

The story of the death is well-known by now: A former Taylor Truman High School valedictorian, Siddiqui, 20, was, according to a Marine investigation, called a "terrorist" and otherwise mistreated by his senior drill instructor, Gunnery Sgt. Joseph Felix, as he began boot camp, threatening suicide but quickly recanting, saying he only believed it was a way to get out and to stop from being hit.

But early on March 18, 2016, after the recruit complained of a sore and bleeding throat, Felix ordered Siddiqui to run laps in the third-floor barracks. When Siddiqui collapsed, Felix — who was already under investigation on accusations of abusing another Muslim recruit whom he had ordered into a dryer the previous summer — smacked him. Siddiqui, at approximately 5:45 a.m., got up and ran out an exterior door, leaping over a stairwell rail, crashing to the ground.

Even though an investigation directly linked Felix’s actions with Siddiqui’s death, the same investigation called Siddiqui's death a suicide and Felix wasn’t charged in connection with it. At Felix’s court-martial late last year on charges of having abused and mistreated recruits, including Siddiqui — charges for which Felix was sentenced to 10 years’ confinement — all mention of the specific circumstances surrounding Siddiqui’s death was barred from testimony.

Siddiqui's family, meanwhile, has spent much of the last 25 months trying to uncover those circumstances in order to learn the whole truth about what happened and to show that the coroner doesn't have evidence to justify a finding of suicide.

The Free Press recently reviewed many of what appeared to be medical records about Siddiqui's treatment received by his family. In doing so, they did not allow copies to be made or names in the documents to be used. The records reviewed also did not include those newly sent by MUSC.

The records that were made available appeared to indicate that, particularly at Beaufort Memorial, serious efforts were made to save Raheel’s life — a chest tube inserted, a blood transfusion undertaken, drugs administered — and that he was then sent to MUSC for a thoracotomy, a chest surgery often used in cases of serious chest injury, with it being seen as his "best chance for survival."

Without being able to see the MUSC records, it is impossible to determine how "questionable" the entries seen by the Siddiqui family were, just as it is difficult to ascertain how "extensive" the hospital's treatment was, though a medical examiner used that phrase to describe the treatment in the autopsy report.

But inconsistencies and questions still remain in the records.

Since medical personnel and others in Beaufort County and Charleston declined to discuss the records, it is hard to judge whether the inconsistencies can be explained, or, as the family believes, they may point to some kind of cover-up.

Some — like the lines on the medication report that seemed to say Siddiqui was "currently pregnant" and "currently breastfeeding," for instance, may have been standard prompts on a form to be checked by medical personnel when dealing with patients.

And while Heather Woolwine, a spokeswoman for MUSC, couldn't discuss Siddiqui's case, she said there are instances where a trauma patient might be misidentified because of some error.

"There can be misspellings. A person can look at a letter quickly and think they recognize it accurately ... and then make a mistake," she said. "Those situations are rare but they do happen."

Other medical experts — including those at the University of Michigan Medical School — declined to speak even generally about the accuracy of medical records in an emergency room situation without being able to see the records themselves.

Khan said the family refuses to believe the inconsistencies are a matter of "confusion" and has even begun to believe that Siddiqui was dead at the moment he hit the ground — a claim that, if true, would throw into doubt all the records that followed, though their reasons for believing that, other than the time of death listed on the death certificate, are not entirely clear.

So far, Khan and the Siddiqui family have also declined to say what specific claims they might try to bring against specific parties — though they could make a decision as early as this week.

But if they do decide to bring claims, the family could find a difficult legal road ahead. Even as their lawsuit against the Marines could run against strict legal doctrines against bringing suits involving active-duty personnel, local officials — under South Carolina law, as well as many other places — typically enjoy limits on their liability in the exercise of their official duties, including in exercising professional judgment.

Khan said, however, that the family can and may challenge the authenticity of the records they’ve received — and the story they’ve been told — in court.

“The law itself allows us to take action against those who have wronged us,” Khan said.

He said the errors and gaps in the record — as well as problems with times and places in the death certificate itself — bolster the family's belief that the cause of death should be changed.

“In light of all that has been discovered, how can you expect the family to believe that he actually took his own life? There’s no record of it," he said.

Contact Todd Spangler: 703-854-8947 or tspangler@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter at @tsspangler.