afe injection sites for drug users may be an option for cities in Michigan looking to slash the skyrocketing rate of overdose deaths and the spread of drug-related diseases.

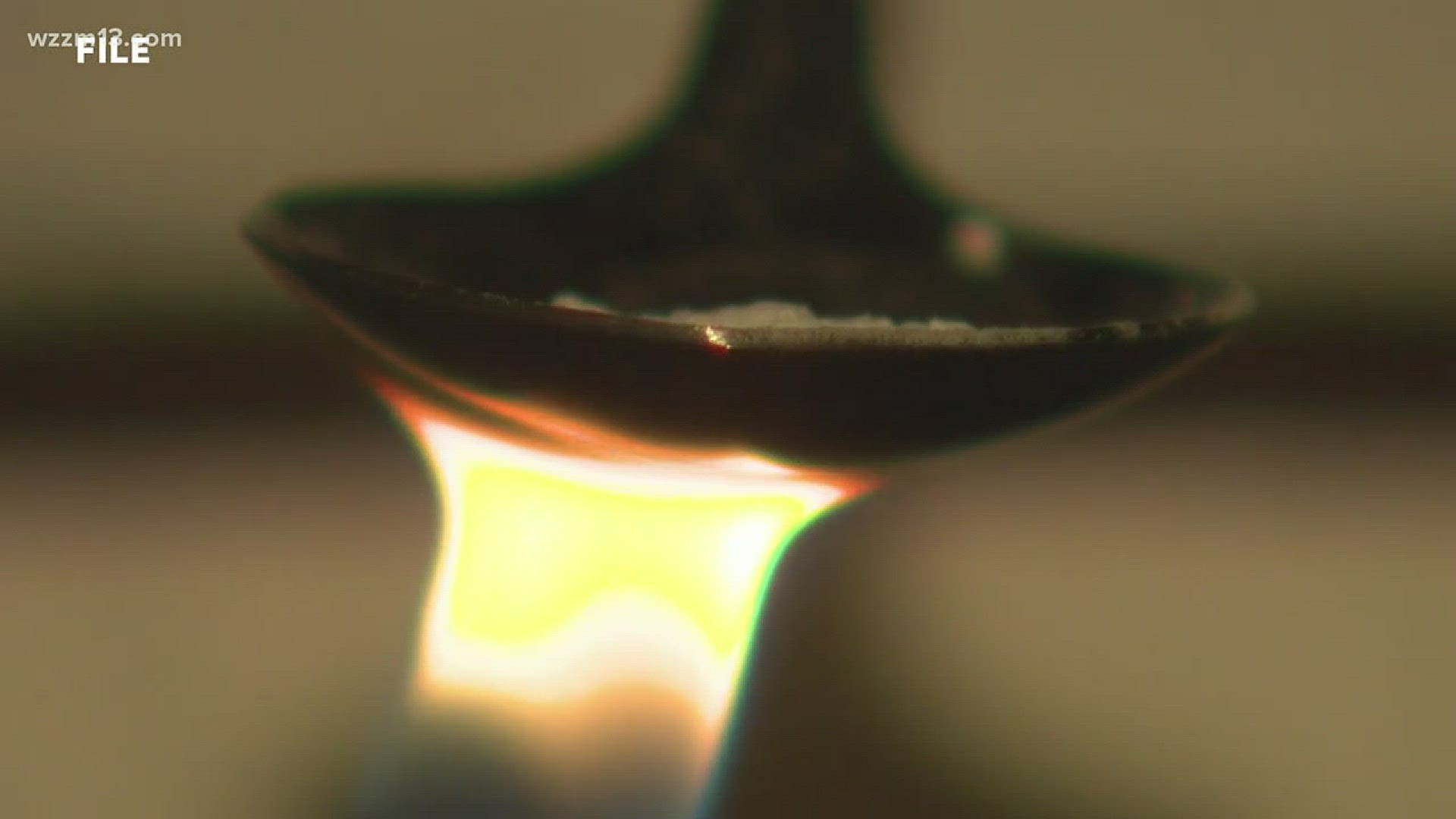

In response to a staggering opioid-related death rate, Philadelphia became the first U.S. city to approve privately run safe injection sites in January. The sites allow users to inject illicit drugs under the supervision of a medical professional, ensure a sanitized space, clean needles and immediate response in case of accidental overdose.

It's a practice known as "harm reduction."

Local health experts said the strategy is worth exploring.

In Detroit, Health Department Director Joneigh S. Khaldun said the city is open to the possibility of safe injection sites.

"Given the alarming number of deaths from the opioid epidemic, as well as the rising levels of Hepatitis C and the recent Hepatitis A outbreak, it is important we consider all options when it comes to protecting some of our most vulnerable residents," Khaldun said in an email. "Harm reduction methods around drug use, such as providing clean needles or safe places to use, are promising options. We are aware of what they are exploring in Philadelphia and that it took a considerable amount of time to research before getting to this point.

"This is a very complex legal and public health issue, but one certainly worth exploring to see if this approach is one that would make sense in our city.”

Talk of how cities can combat the ongoing opioid epidemic differently, comes on the back of troubling overdose numbers rising across the country — with no signs of slowing.

Deaths from drug overdoses totaled 64,070 for the 12 months ending in January 2017, up 21% from the same period a year earlier, when the death toll was 52,898, according to the the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Michigan Department of Health & Human Services reported 2,356 Michiganders died of drug overdoses in 2016, more than the number of deaths in traffic accidents.

Proponents of safe injection sites argue the facilities could be a means to connect directly with opioid users, provide education to help users kick the habit, reduce overdose deaths and curb the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV and Hepatitis C by ensuring sanitary conditions and clean needles.

Opponents worry the sites enable opioid users to inject illicit drugs legally and could lead to increased criminal activity and drug use.

Yet, the U.S. lags behind other nations when it comes to the use of safe injection sites in combating the opioid epidemic.

According to the Massachusetts Medical Society: The first official, legal safe injection site opened in Switzerland in 1988. A site was opened in Sydney, Australia in 2001 and Canada opened its first facility, called Insite, in 2003. By 2014, there were approximately 90 safe injection sites active worldwide.

A comprehensive study of safe injection sites conducted by MMS in April found no deaths by overdose have been reported at these facilities and the opening of a site was not associated with an increase in crime or an increase in the number of opioid users.

This decision from Philadelphia was backed strongly by its mayor and district attorney, according to NPR, and it appears to be the beginning of a broader movement. City officials from Seattle and San Francisco have also been considering approval of safe injection sites.

State Rep. Hank Vaupel, R-Fowlerville, who chairs the state House Health Policy Committee, said opening sites in Michigan would require a big change in legislation.

“I would much rather see a safe, clean space where someone can come and be held harmless to dispose of the drugs and needles they have, and get medical counseling," Vaupel said. "That would be preferable, not a place where they can continue to illicitly use drugs."

But many substance abuse experts in Michigan said the possible benefits of safe injection sites may be worth it.

Henry Ford Health substance abuse specialist Elizabeth Bulat said it would take a lot more legal and medical investigation before Michigan is ready to approve safe injection sites, but it could be a valuable option.

“When we look at substance use … we look at sort of two pathways," she said. "One is, our goal is always abstinence, We want patients to get sober and a life of recovery, but sometimes we have to do the harm reduction path to get to abstinence.”

Bulat noted that safe injection sites aren't the only controversial harm reduction approach aimed at reducing opioid-related deaths.

Needle exchange programs, for example, have been active in Michigan for years because of local exemptions and changes in city ordinances.

Although syringes are classified as prohibited drug paraphernalia under state law, local governments and public health agencies have been allowed to authorize the distribution of sterile syringes, said Steve Alsum, coordinator of the Clean Works needle exchange program in Grand Rapids.

Since beginning in 2000, Alsum said the program has helped reduce the number of HIV/AIDS cases related to injection drug use in Kent County from 25% in 1988 (when a task force first recommended needle exchange) to 8%.

Alsum said safe injection sites could provide equal benefit.

"While this service can't legally be provided in our state at this time, we would be very interested to form a coalition to advocate for their establishment in Michigan, and Grand Rapids specifically," he said.

"With the number of people dying in our state right now, it's high time we get over our moralistic qualms, and start providing evidence-based programming to keep people struggling with opioid use alive."

Yashica Ellis, client service coordinator for Wellness Services, Inc., which runs a needle exchange program in Flint, agreed.

"Safe injection sites have bee in place in Europe for over 30 years," Ellis said. "Data shows these sites have been found to reduce HIV and Hep C, reduce the number of overdose deaths and reduce the number of improperly disposed of syringes, while increasing the number of individuals entering into detox or treatment. Wellness Services find this to be encouraging."

Barbara Locke-Jones, director of finance and prevention at the Community Health Awareness Group which offers needle exchange via their Life Points Harm Reduction Outreach Program, said city ordinance had to be changed prior to their operations.

Needle exchange participants are required to be registered with the city and given a license. Thus, while their organization does focus on and support harm reduction, Locke-Jones said safe injection sites would have to work with many players before taking off.

"If safe injection sites were something that was the direction Detroit took, it would require a similar public-private partnership approach that led to the creation of the current paraphernalia ordinance," she said. "It would have to include the community at-large, public health officials, medical professionals, the substance abuse community and law enforcement if that was a direction that the city were to take."

At the end of the day, Henry Ford's Bulat said harm reduction strategies are an opportunity to decrease health risks.

“This is a disease of decision-making, it really hijacks the patient’s brain. So, I think overall, they’re not themselves anymore. And they will really do anything to get drugs, and usually it consumes everything,” she said. “So, the goal is to get patients to get help before that happens or before death or before jail.”

Joe Schrank, a safe injection site advocate and founder of the California-based cannabis inclusive recovery program High Sobriety, said cities like Detroit should join Philadelphia in leading the way.

“It’s a hard thing for people to get their minds around, because it seems like we’re giving in or we’re supporting drug use. We’re not doing that in any way. We’re re-thinking how to handle this problem," he said.

"Not having (safe injection sites) doesn’t mean that people don’t inject, it means they inject with infected needles and they spread HIV, Hep C, other diseases. They do it in Starbucks bathrooms, between cars, it’s really a lot of collateral damage for the community."

Contact reporter Aleanna Siacon at ASiacon@freepress.com, Follow her on Twitter @AleannaSiacon.