The medical marijuana industry is poised for explosive growth in Michigan. And new laws seeking to regulate, tax and legitimize the lucrative business have unleashed a torrent of cash at Lansing decision makers, sending dozens of lobbyists, lawmakers, legislative staffers and business owners scrambling for a piece of the billion-dollar enterprise.

All the jockeying is taking place under Michigan's weakest-in-the-nation laws outlining government ethics, transparency and conflicts of interest. And it’s happening while Lansing awaits Gov. Rick Snyder’s appointment of a five-member board that will ultimately oversee licensing of the industry, raising questions about who will truly benefit from bringing pot to the mainstream.

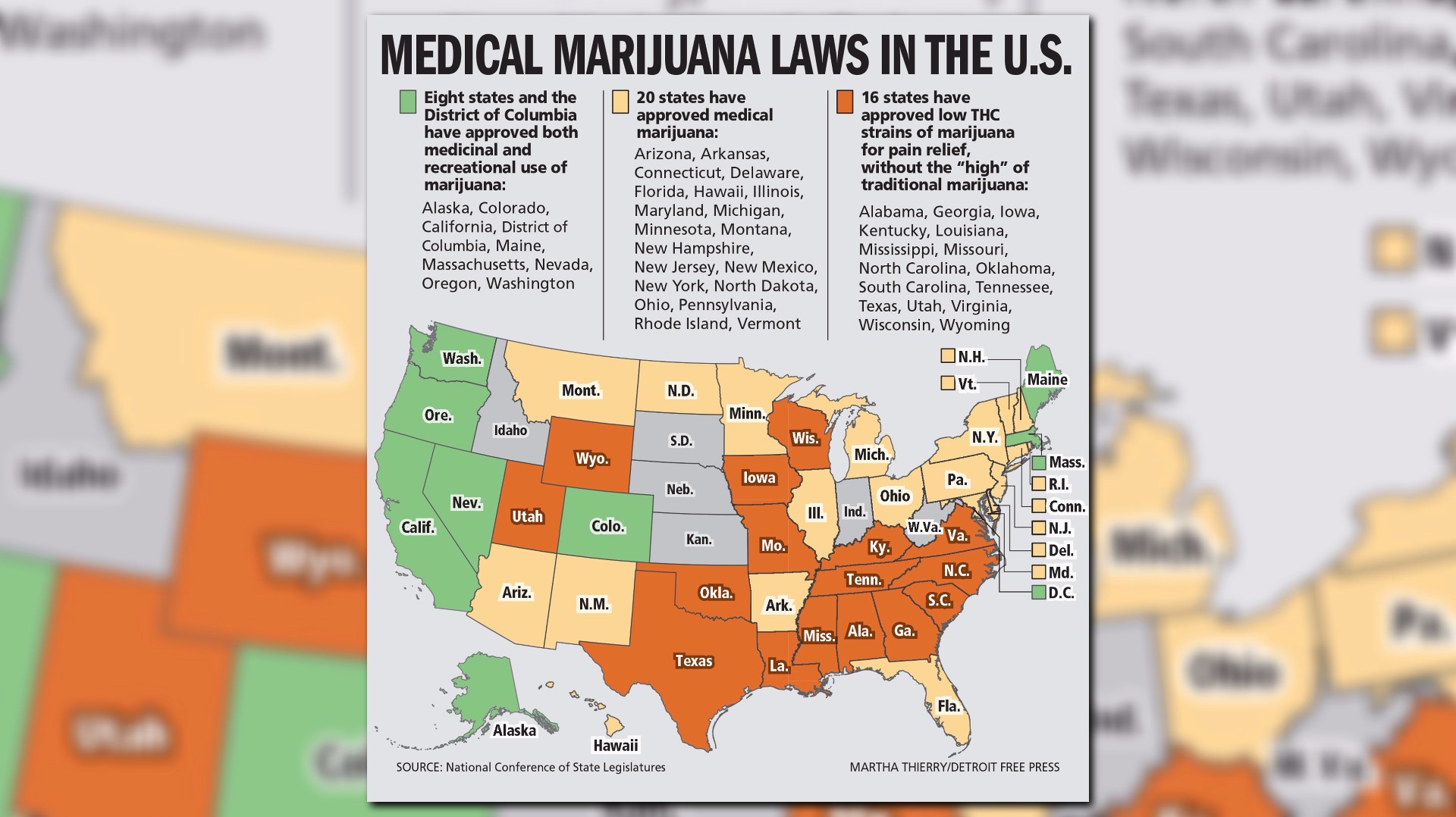

The stakes are high: While medical marijuana revenues in Michigan are estimated at more than $700 million, if full legalization of marijuana happens, as it has in eight other states, the revenues could be enormous. Arcview Market Research, a California-based company that tracks the marijuana industry, reported $6.8 billion nationally in legal marijuana sales — both recreational and medicinal — in 2016, and projects the market to grow to $21.6 billion by 2021.

Amid those types of numbers, the lobbying efforts in Lansing have exploded.

A Free Press investigation found:

- The chiefs of staff of the House and Senate committees developing the medical marijuana legislation both quit their jobs in the past two years to become lobbyists for the medical marijuana industry.

- Former House Speaker Rick Johnson, a lobbyist since 2005, worked on the medical marijuana legislation though he said he had no paying client, and has now been nominated to be on the five-member board that will issue lucrative medical marijuana licenses.

- Johnson also is negotiating the sale of his stake in the lobbying firm, Dodak Johnson & Associates, to a lobbyist for the medical marijuana industry, raising concerns about whether industry lobbyists could seek to curry favor with Johnson through the price paid.

- Since 2015, medical marijuana interests have spent more than $336,000 lobbying state lawmakers and officials and have paid more than $50,000 into campaign funds state lawmakers control. The actual numbers are higher, but can't be calculated from public records because state law does not require multi-client lobbying firms — including some whose client lists include medical marijuana players, according to a review by the Free Press — to identify how much of their total lobbying effort is spent on a specific issue, such as medical marijuana.

- While campaign fund donations must be publicly reported, lawmakers don't have to disclose donations businesses make to federal nonprofit funds they control, known as "social welfare" organizations.

- According to a filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, former House Rep. Eileen Kowall, R-White Lake Township, received $15,000 worth of shares in a medical marijuana company in 2015 to pay for consulting work, while her husband, Senate Majority Floor Leader Mike Kowall, R-White Lake Township, helped push medical marijuana bills through the Legislature. Elaine Kowall confirmed to the Free Press she signed the agreement and received the shares, but said she quickly recognized the conflict of interest, rescinded the agreement and returned the shares.

The developments have largely been shielded from public view. Michigan has no financial disclosure requirements for public officials, minimal restrictions on lawmakers or legislative staffers working in the Capitol one day and hanging shingles as lobbyists the next, and weak lobbying reporting laws.

"If you’re potentially going to be on the payroll of a company interested in a bill you’re pushing, that presents huge problems," said David Vance, spokesman for Common Cause, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that advocates for more accountable government. "If someone stands to make a significant financial windfall, they may be inclined to do favors for future employers."

The Center for Public Integrity, an investigative news organization that has ranked Michigan 50th in the nation in terms of transparency and accountability, said the issues surrounding the regulation of the medical marijuana industry should make Michigan and other states strive for more transparency.

"The issues here highlight a broader reality that state legislatures are not paragons of disclosure and protections against conflicts of interest," said Gordon Witkin, executive editor at the center. "There’s lots of money in marijuana and as legalization continues to proliferate, we’re going to see more cash and more questionable behavior."

Rick Thompson, a medical marijuana advocate and board member of the Michigan chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, said he was disgusted by the process that culminated in approval of a five-bill package in September.

"One of the positives of the Trump administration is his ban on going immediately from government to lobbying and that's something Michigan should emulate. Influence peddling is such a deep-rooted part of our legislative process that it’s difficult to remove from the Capitol," Thompson said.

In addition to the jockeying in Lansing, wealthy businessmen such as developer Ron Boji and entertainment mogul Tom Celani — owner of the Freedom Hill Amphitheatre — are also potentially seeking to get into the medical marijuana business. Both are prolific campaign donors.

'Wild, wild West'

Michigan voters legalized medical marijuana in 2008, but bare-bones regulation of the drug created a "wild, wild West" landscape, with patients concerned about safety, quality and security of supply. Michigan courts ruled that only marijuana sales between registered caregivers and patients were legal, meaning the dispensaries used by many patients shut down frequently and largely relied on local officials in some communities turning a blind eye in order to operate.

That's changing under the package of bills Snyder signed into law in September, which require state-issued licenses for large-scale growers, processors, testers, secure transporters and retailers of medical marijuana and give communities the authority to allow and zone for medical marijuana dispensaries within their borders. Though welcoming the fact that the laws give new legal protections to those who use medical marijuana, some advocates say the new rules set the stage for high prices and near monopoly control by politically connected investors.

"There’s huge money to be made. There have only been two issues that I’ve been lobbied so hard on, and this is one of them," said Sen. Tonya Schuitmaker, R-Lawton, who opposed the legislation, and recalled a health care issue as the other hot-button topic for lobbyists.

The apparent feeding frenzy, observers say, is the result of a rare opportunity to get in on the ground floor of a new and lucrative state-licensed industry. A House Fiscal Agency analysis of the laws says the industry is expected to generate $771 million in annual sales and $21.3 million in state taxes.

Today, close to 250,000 Michigan residents hold medical marijuana cards, many of them are served by nearly 41,000 licensed caregivers, who are each permitted to grow no more than 12 marijuana plants for each of up to five patients. With new ballot drives about to launch to legalize marijuana for recreational use in Michigan, proponents expect many of the regulations placed on the medical marijuana industry to carry over into the recreational market, with potential revenues expected to escalate into the billions.

Now, Lansing awaits Snyder's appointment of the five-member board to oversee medical marijuana licensing. Three of the appointments are Snyder's, with one each recommended by Senate Majority Leader Arlan Meekhof, R-West Olive, who has submitted Johnson's name, and House Speaker Tom Leonard, R-DeWitt, who declined to reveal his nominees. Another 17-member advisory panel will help develop the rules and regulations surrounding medical marijuana.

From chiefs to lobbyists

Much of the grunt work in drafting bills is done by key legislative staffers, and no staffers were more integral to the process than the chiefs of staff to the two judiciary committees that worked on the legislation.

Brian Pierce, who was chief of staff to House Judiciary Chairman Rep. Klint Kesto, R-Commerce Township, and Sandra McCormick, who was chief of staff to Senate Judiciary Chairman Sen. Rick Jones, R-Grand Ledge, both now have better-paying jobs as lobbyists for the medical marijuana industry.

Pierce left the Legislature in November 2015, less than two months after the medical marijuana bills cleared the House of Representatives, and registered as a lobbyist in December with only one client — the Michigan Responsibility Council, a medical marijuana trade association representing businesses who want to get involved as growers.

McCormick, who was chief of staff to Jones, became executive director in January of the Michigan Cannabis Development Association, which is funded by businesses that want to get a medical marijuana license once the state starts awarding them in December.

The two staffers said they see nothing wrong with the move to lobbying and that it is typical of what happens in Lansing, especially in an era of term limits when staffers are forced to move when their boss has to leave office.

"You see that all the time," Pierce said. "Think of all of those who are in leadership roles now; they’ve all come from staff at one point or another."

McCormick said she had a choice: stay two more years in the Legislature or move to a job that would have more longevity.

"I can't count how many policy advisers have left the Legislature to a policy area that they really like," she said.

The staffers' former bosses said they also have no problem losing their employees to businesses they've directly impacted through legislation they've sponsored.

"There is only so much money to be made here — $40,000 is the average," Kesto said. "They’re going to go where their niche is and work on something that they understand."

Jones said McCormick is the third chief of staff that he has lost to lobbying.

Aaron Scherb, director of legislative affairs for Common Cause, said a cooling-off period for elected officials and office staffers would prevent actual impropriety or even the appearance of impropriety. Currently, both the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, as well as 34 states, have rules in place that prohibit lawmakers from becoming registered lobbyists for a period of time, usually one or two years. In addition, seven states and Congress have established cooling-off periods for a variety of legislative staffers.

"Government service should be done to promote the public interest, not as a stepping stone for profit or to line one's pockets," Scherb said.

Both Pierce and Johnson also told the Free Press that Pierce is seeking to buy Johnson's firm, though nothing has been finalized. Pierce's firm, Philip Alan Consulting, had set up shop in the same suite of offices as Dodak Johnson and Associates, a lobbying firm started in 2005 by Johnson and former Democratic House Speaker Lew Dodak.

How it works

Under state law, active lobbyists are ineligible for appointment to the state's medical marijuana licensing board. Johnson, who dropped his lobbyist registration on Nov. 30, is still listed as treasurer at the Dodak Johnson lobbying firm. He confirmed he's now in line to get an appointment to the medical marijuana licensing committee.

“I would do that, because it’s non-pay,” and as someone who is retiring, “I’m in a position where I’m able to do it,” Johnson said.

He said he helped put together the medical marijuana legislation, but didn't get paid by any client for the free advice he gave, noting he wanted to assure easy and affordable access for patients, including relatives and friends who have benefited from the use of medical marijuana.

“People asked me: ‘What do you think about this?’” and I would tell them, Johnson said.

Johnson wasn't specific about who he advised, but said among them was Pierce when he was still the chief of staff to Kesto, giving Pierce free advice on legislative matters and how to get bills through committee. Later, when Pierce decided to leave Kesto’s office and set up his own lobbying firm, Johnson said he told Pierce there was space they could rent in the Dodak Johnson suite in downtown Lansing.

Johnson denied any conflict of interest, saying he has never done "anything for anybody" where a conflict existed. He said he wouldn't have a vested interest if appointed to the licensing board, saying all he cares about is the patients.

“I didn’t get into this business to make a bazillion dollars,” said Johnson, adding that his main retirement plans are to return to his farm in rural LeRoy.

But he does stand to benefit from the sale of his lobbying firm — possibly to Pierce.

At the Michigan Responsibility Council, president and CEO Suzie Mitchell said Johnson would still be a good choice for the licensing board. "Lansing is Lansing — people retire," she said. "This is how the process works."

Others disagree. Jones, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said he has nothing against Johnson but "I would like the board not only to be squeaky clean, but to have an appearance of no problems at all ... I oppose any lobbyist or former lobbyist being on the board."

Consulting contract

As Senate Majority Floor Leader, Kowall, R-White Lake Township, made the motion in September to discharge to the full Senate the package of medical marijuana bills that had been stalled in the Senate Judiciary Committee for nearly a year. He made no disclosure about any dealings between his wife, Eileen, and a medical marijuana company.

A Feb. 20, 2015, a consulting contract between Eileen Kowall and Michigan Green Technologies — dated less than two months after the former lawmaker left the Michigan Legislature because of term limits and one day after she registered as a lobbyist — was filed with the SEC in April 2015 by Cannabis Science, a publicly traded medical marijuana company headquartered in Colorado, with a major ownership stake in Michigan Green Technologies.

The agreement promised to pay Kowall 300,000 restricted common shares in Cannabis Science, which then had a market value of $15,000, upon execution of the agreement, plus future expenses and possible stock options and bonuses through the life of the contract, which extended to Feb. 15 of this year.

Mike Kowall told the Free Press Tuesday that his wife never signed the contract or received the shares.

"It would have been a conflict of interest, and that's why she didn't do it," Kowall said.

But on Wednesday, Eileen Kowall confirmed she signed the agreement and received the shares after she was introduced to Michigan Green Technologies official John Dalaly through "mutual friends" and as a result of her work on medical marijuana bills — she sponsored a bill to legalize non-smokable forms of marijuana — when she was in the Legislature.

"I can tell you that it was over as soon as it started," and she returned the shares within "a few days," because "there could be very definitely a conflict" with her husband's work in the Legislature. "It was a dumb mistake," she said. "I rejected that contract, but unfortunately they had already filed it" with the SEC.

In fact, it was two months after the date of the contract, in a 10-K report to the SEC dated April 21, 2015, that Cannabis Science reported the consulting agreement with Kowall, making no mention of the contract being rescinded or the shares returned.

Eileen Kowall on Thursday produced a March 28, 2015, letter from her to Michigan Green Technologies, resigning as a board member "due to unforeseen circumstances." She said she verbally resigned "a few days" after signing the agreement, and enclosed her stock certificate with her resignation letter, having done no consulting work. She also forwarded a March 2, 2016, e-mail from Dalaly to a Cannabis Science official, saying Kowall's stock certificate "was shredded by me per instructions about a year ago."

Michigan Green Technologies is no longer in business, said Dalaly's Troy attorney, Daniel McGlynn.

Dalaly also made $400 in campaign donations to Mike Kowall in November 2015 while the contract with Eileen Kowall was in place, state campaign finance records show. That $400 was part of $1,400 that Dalaly and his wife, Dina, gave in 2015 to key lawmakers involved in the medical marijuana legislation.

The agreement filed with the SEC said Eileen Kowall was paid for business advice, outreach, crisis management, strategic planning and "assisting with government relations, lobbying and public relations."

Neither Eileen Kowall nor the firm she works for, MGS Consultants of Lansing, registered with the Secretary of State's office as a lobbyist for Michigan Green Technologies, records show.

Lack of disclosure

Four lobbying firms or associations that are solely tied to medical marijuana spent $336,277 on trying to influence lawmakers on the issue in 2015 and 2016, records show. They are the Michigan Responsibility Council, which spent $146,000; the Michigan Cannabis Development Association, which spent $124,514; the National Patient Rights Association, which spent $37,969, and Prairie Plant Systems, which spent $27,794.

However, it’s hard to get a true sense of how much other lobbying was going on because of the lack of disclosure laws in the state, said Craig Mauger, executive director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, noting the money from the marijuana trade associations" is probably only a fraction of what was actually spent.”

For example, the MCDA's lobbyists included GCSI, one of Lansing's largest multi-client firms, which doesn't have to itemize how much it spends on an issue-by-issue basis.

Kesto and marijuana bill sponsor Rep. Mike Callton, R-Nashville, were the top two recipients in the Legislature of meals and drinks paid for by Michigan lobbyists in 2016, with Callton receiving $4,047 in food and drink and Kesto getting $3,266, according to the Michigan Campaign Finance Network. The biggest provider of those freebies was GCSI, records show.

In addition to most of the lobbying firms in Lansing being involved in lobbying on the issue on behalf of a myriad business interests and patient groups, Mauger said groups like the state sheriffs' and prosecutors' associations also tried to influence the end product.

“And the public has no idea, which is extremely problematic,” he said.

Receiving medical marijuana campaign funds since 2015 were: Kesto, whose campaign fund and PAC received at least $15,175; Jones, whose state funds received at least $15,000 and who told Fox 2 he also received $5,000 in marijuana funds in a federal nonprofit fund that does not report its donors; marijuana bill sponsor Callton, whose state campaign fund received at least $4,250, and Mike Kowall, whose state funds received at least $2,800. State funds connected to Senate Minority Leader Jim Ananich, D-Flint, received at least $1,750.

Kesto, Jones and Meekhof said the campaign donations were above board and properly reported.

"Everything I did was within the law and within the campaign finance rules. We didn’t do any quid pro quo," Kesto said. "Over the past three election cycles, I raised maybe a million dollars, so that amount was a drop in the bucket."

Big operators

Despite the infusion of cash, legislators resisted suggestions to limit the industry to the biggest businesses.

"There were moves to monopolize all the testing and distribution, moves to monopolize the growing," said Callton, who sponsored the primary bill in each of his three sessions in the Legislature. "Even now you see some big out-of-state operations that want to come in and grow hundreds of thousands of plants."

There are fears the big operators in the industry will squeeze out current caregivers and that patients will be left with an unaffordable product.

Robin Schneider, who became a medical marijuana patient after suffering a stroke in 2013, is now the executive director of the National Patients Rights Association. She started trying to get a bill passed even before her stroke when a cancer-stricken friend was desperate for a non-smokable form of marijuana that could be put in his feeding tube.

Four years later, after multiple hearings, work group sessions and fights over the final legislation, she just wants to make sure that patients' needs don't get lost in the rush for licenses and the quest for profits.

"Our concern is that regulations are reasonable enough that licenses aren’t impossible to get and at the same time avoid a monopoly in the business," she said.

The group didn't get everything it wanted, she said. Schneider would have liked a better opportunity for current caregivers to transition to the new system and a requirement that anyone applying for their first license be a caregiver with at least two years of experience.

"But we accomplished our goal of mandatory testing and access. We’re not unhappy with the result," she said. "We just hope that the regulation will allow small business and affordable products."

That was Callton's goal, too, when he first introduced the bills.

"There were people who tried to figure out how to corner the entire industry by leveraging the Legislature," he said. "But I would rather see 1,000 millionaires than one billionaire created from this act."