On March 22, 2017, General Motors' factory worker Mark Edwards was headed for his work area inside the company's transmission plant in Toledo, where he has worked since 2014.

Edwards, a 59-year-old black man, turned the corner, heading into his department and was met by an unbelievable sight: Someone had hung a noose by his work station.

"I was startled, really startled by it," said Edwards, who took a picture of it. "I couldn’t believe someone did that. I couldn’t understand who in my work area disliked me that much or had that much hatred to hang a noose by my job."

Mark Edwards, 59, plaintiff in a lawsuit against his employer GM is photographed at Roy, Shecter and Vocht, in Birmingham on Wednesday, Nov. 28, 2018. (Photo: Kathleen Galligan, Detroit Free Press)

Edwards, who has worked for GM in various plants since 1977, said he has endured racial slurs and harassment for years from coworkers. He reported each incident to his union reps and managers. He said nothing was done to end it.

The noose was too much, though. Edwards said that in 1968, his then-19-year-old brother was tied up by rope and beaten in a racially motivated attack. It left his brother brain-damaged, he said.

“That rope took me right back," Edwards told the Free Press. "I thought of my whole childhood again, being afraid and having to know I had to be strong.”

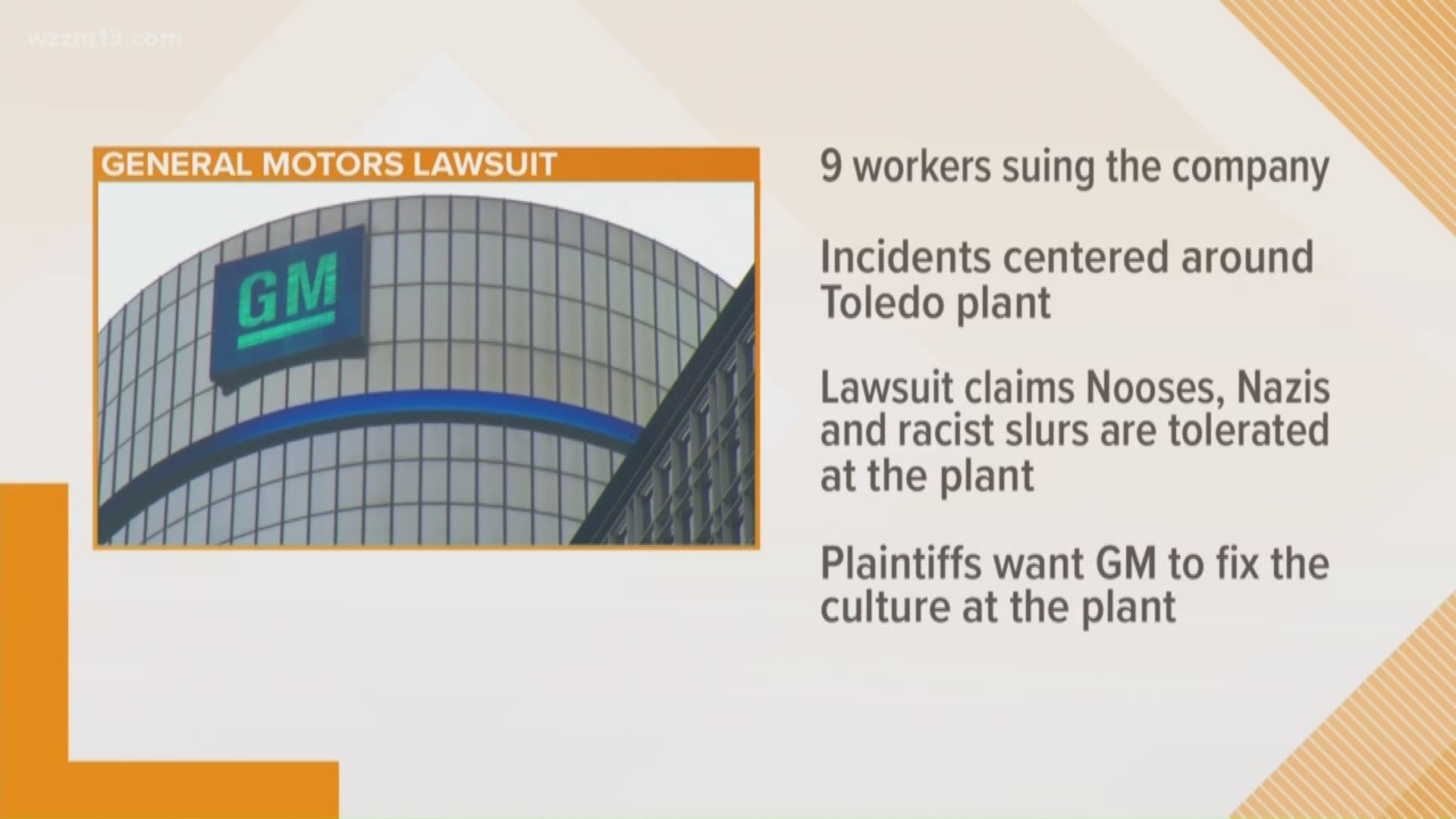

Edwards and eight other black workers are suing GM, alleging the company has allowed racial discrimination and has failed to take prompt corrective action after the workers reported acts of racism at the GM Powertrain & Fabrications plant. Some, like Edwards, still work there. Others have quit or transferred to other GM plants.

A noose found on March 22, 2017 at GM Powertrain & Fabrications plant in Toledo. This is one of three nooses allegedly found at the plant. A group of black employees are suing General Motors for allowing alleged racism. (Photo: Mark A. Edwards)

The suit seeks compensation for lost wages and mental pain. Beyond that, the plaintiffs want GM to fix the culture at the plant.

For its part, GM said it has taken several steps to address improper behavior, even stopping production to train workers on anti-harassment and anti-discrimination policies after the noose was found.

"Discrimination and harassment are not acceptable and in stark contrast to how we expect people to show up at work," said GM in a statement. "General Motors is taking this matter seriously and addressing it through the appropriate court process."

Nooses and the Klan

About 1,700 people work at the plant in Toledo. They build 6-speed and 8-speed rear-wheel-drive transmissions and 6-speed front-wheel-drive transmissions for GM trucks, sedans and sports cars.

The lawsuit, filed on Sept. 21 in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, states that about 11:35 p.m. on March 22, 2017, three nooses were found hanging from the ceiling and a valve in the Casing Machine Department.

In April and May, the lawsuit alleges, two more nooses were found hanging in the plant's assembly room, one of which a black worker reported to his supervisor.

Nooses symbolize lynching, a form of racial terrorism that escalated in the U.S. in the late 1800s and tapered off in the 1920s.

Workers wrote racist graffiti on bathroom stalls and walls at GM Powertrain & Fabrications plant in Toledo, said a lawsuit against General Motors. (Photo: Mark A. Edwards)

The nooses set off a chain of racially charged actions by white workers against black employees at the plant, the lawsuit said. In June 2017, for example, a white employee threw a rope that resembled a noose at a black employee. GM suspended the white employee for 30 days "under the horseplay rule," the lawsuit said.

The lawsuit described various other alleged incidents of racially hostile remarks and epithets in the last four years, including:

- White employees calling black employees "boy."

- A female black employee being called a crude, racist slur.

- Swastikas painted and scratched on restroom stalls.

- Stick figures with nooses around their necks drawn on restroom stalls.

- White workers wore shirts under their coveralls with visible Nazi symbols on them.

- Black employees told to be careful because a white employee's "daddy was in the Ku Klan Klan."

- White workers telling black workers to go back to Africa.

- "Whites Only" signs hung on restroom stall doors and written on walls outside the men's restroom.

- A white supervisor, at a meeting, saying, "What's the big deal about nooses? There was never a black person who was lynched that didn't deserve it." The supervisor was not disciplined, the lawsuit said.

GM's reaction

The alleged behavior did not just target black workers.

In one instance, a white woman running for a union office happened to be dating a black man, the lawsuit said. Her election posters throughout the plant were, "defaced with racial slurs and drawings of black penises," the lawsuit said.

The lawsuit said because GM failed to take prompt corrective action in all the incidents, it created "an atmosphere whereby hate-driven employees felt free to hang nooses, display racist graffiti, and verbally attack and racially insult African-Americans. These symbols of the historical torture and lynching of African-Americans touched each of the plaintiffs, were a personal affront to each's dignity and caused each fear for his or her safety."

GM said it treats "any reported incident with sensitivity and urgency, and (is) committed to providing an environment that is safe, open and inclusive."

GM said it worked with union leaders on a memo it handed out to plant workers on April 12, 2017. The memo referenced an "incident" that was "offensive to all employees." A GM spokesman confirmed that "incident" was the noose Edwards found on March 22.

The memo said GM has zero tolerance for workplace violence or harassment, particularly if it relates to race, sex, ethnicity, age, religion, national origin, disability, sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. It also instructed on multiple ways to report problems.

GM said it also did the following:

- GM conducted ongoing reinforcement of its zero-tolerance policy through all-employee meetings, small team meetings and newsletters.

- Additional anti-harassment and anti-discrimination training took place for all employees in Toledo, jointly with the UAW, in which production was stopped and all employees attended. This training also instructs employees on how to report and react to incidents.

- Other GM plants conducted similar anti-harassment and anti-discrimination training in 2018, jointly with UAW.

Civil rights ruling

Prior to filing the lawsuit, four of the plaintiffs filed complaints with the Ohio Civil Rights Commission starting on May 31, 2017. In the complaints, they described the nooses and the other incidents of racist actions.

In the commission's report, UAW local President Ray Wood said that after finding the first noose in March 2017, he met with the plant's human resources' director and plant manager on "how to move forward." He told the commission that his suggestions "fell on deaf ears."

This past March, the commission found probable cause that "GM engaged in unlawful discriminatory practices." The commission denied GM's request in April for reconsideration.

It ordered GM to "immediately provide its employees with an environment free of harassment, intimidation and hostility."

It ordered GM to establish an equal employment officer to train employees on anti-discrimination laws and write appropriate anti-discrimination policies and procedures for addressing and investigating any future complaints. GM must also establish regular yearly training sessions, with curriculum submitted to the Ohio Civil Rights Commission in advance.

GM said it has no knowledge of racist acts at any of its other plants.

"We did disagree with the commission’s findings," GM spokesman Pat Morrissey said. "We fully cooperated with the investigation. This matter is no longer with the commission and has moved into litigation.”

Action over money

Edwards and the other plaintiffs want "similar remedial relief as the OCR ruled because our clients are firm that they are engaged in the litigation to exact real change in the culture at GM," said Michelle Vocht, the plaintiffs' lawyer and partner in Roy, Shecter & Vocht in Birmingham.

This lawsuit wants GM to "immediately" make the workplace free of harassment, intimidation and hostility and fire those responsible for it. It asks that GM take security measures including cameras or increased surveillance of the plant floor and that GM immediately remove any racist graffiti.

Like Edwards, Kenny Taylor, 58, has worked at various GM plants since 1978. He still works at the Toledo plant, where he has been since 2014, even though he is part of the lawsuit against GM. He saw the noose left by Edwards' area, but he has endured his own problems too, he said.

"When I’d go to the bathrooms, I saw Nazi symbols on the walls and 'Hate blacks' and “Blacks shouldn’t be here,' " Taylor told the Free Press. "It hasn’t gotten better, it’s gotten worse because when you start complaining about stuff, nothing gets done. You tell your union supervisor and nothing gets done.”

Taylor said he was in an employee room in April 2017 with Edwards. Edwards was seated at a computer monitor checking his pay stub when a white co-worker approached and said, "You’re in my chair (N-word).”

"He proceeds to pull the chair from up under me, I caught myself before I touched the ground," Edwards said.

He and Taylor say they reported it to the union and the plant's human resources. "They said they would investigate and get back to me and they never did," said Edwards.

Taylor and Edwards have bills to pay and are too young to retire, they said. So Edwards drives from Detroit and Taylor drives the 40-some miles from his home in Brownstown, to the plant to work. Both admit it is tough in light of the lawsuit, and Taylor has put in for a transfer to a different plant.

"I hate to get off the exit when I’m on my way there, I think, 'What is it going to be like today?' " said Taylor. "You just feel the tension when you pull up in the parking lot. There are Confederate flags on the license plates."

Contact Jamie L. LaReau: 313-222-2149 or jlareau@freepress.com