State workers tasked with ensuring the quality of municipal water systems tried to hush a federal employee who raised red flags about the potential that lead could leach from the pipes in Flint, newly released emails show.

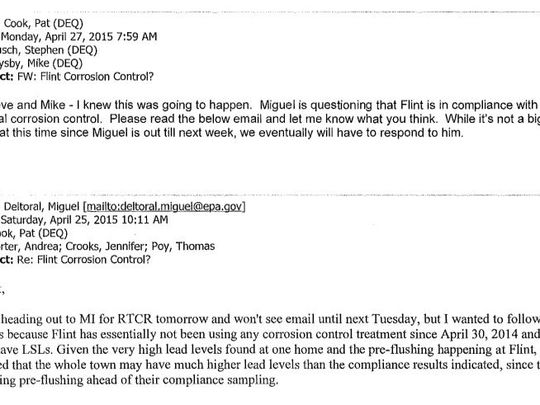

Correspondence within the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality reveals that employees stonewalled Miguel Del Toral, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulation manager who questioned the city's failure to use corrosion-control chemicals in 2014, a doomed cost-cutting move.

“I knew this was going to happen," Patrick Cook wrote in an April 27, 2015, message to co-workers Stephen Busch and Mike Prysby. "Miguel is questioning that Flint is in compliance with optimal corrosion control. Please read the below email and let me know what you think. While it's not a big hurry at this time since Miguel is out till next week, we eventually will have to respond to him.”

The message was sent a year after the City of Flint changed its water source from Lake Huron to the corrosive Flint River and did not add crucial corrosion-control chemicals to prevent lead from leaching into the water.

Busch, district supervisor of the MDEQ's Office of Drinking Water and Municipal Assistance, replied: “If he continues to persist, we may need Liane (Shekter Smith) or Director (Dan) Wyant to make a call to EPA to help address his over-reaches.”

Busch, who was later suspended pending an investigation, also wrote that Del Torall: "continues to base his concern on a single location which has/had a lead service line and 'pre-flushing' concerns which are not part of the current regulations. Flint is now below the criteria for a large system. Technically they don't have to do any of this."

Residents complained about foul smells, discoloration and health effects almost immediately after the city stopped drawing from Lake Huron in late April 2014. Soon after the switch, the water system was besieged with problems. Boil-water alerts were issued for e. coli bacteria contamination. Chlorine was added to control the bacterial growth, which led to an excess of trihalomethans (TTHMs) that cause a wide range of health problems.

The water also may have contributed to outbreaks of Legionnaire's disease, which killed nine people. The most pervasive problem, however, was lead — an odorless, tasteless neurotoxin.

Still the MDEQ held firm that the water was safe despite the lack of corrosion-control measures similar to what was in place before switching to the Flint River water. Without the use of phosphates, the corrosive water began to eat away at the city's lead-laden pipes, joints and fixtures, allowing the toxic metal to leach into the public drinking water, poisoning residents.

Even when the city's testing showed high levels of lead in the tap water of a resident's home, MDEQ officials were quick to dismiss it.

Jennifer Crooks, Michigan program director for ground and drinking water from the Region 5 EPA office, sent this Feb. 26, 2015 email to Busch and Prysby: "WOW!!!! Did he find the LEAD! 104 ppb. She has 2 children under the age of 3… Big worries here."

Prysby insisted it was an isolated incident likely due to the home's own pipes, noting that all other water samples were below the action level for lead.

Busch forwarded the correspondence to his boss, Shekter Smith, saying: "Not sure why region 5 sees this one sample as such a big deal."

Of course, it wasn't only one sample. Later testing by whistle-blowers revealed that high lead levels had been poisoning residents for months.

Staff Writers Todd Spangler and Paul Egan, Nancy Kaffer, Elisha Anderson, Jennifer Dixon, Matthew Dolan, Kathleen Gray and Keith Matheny contributed to this report.