OTTAWA COUNTY, Mich. — It was early 2016 in the main conference room of the Ottawa County government's Fillmore Complex when Ottawa County Clerk Justin Roebuck remembers being faced with an unexpected narrative.

"I remember getting questions from the folks who were in the room about whether or not they could trust that the vote was going to be counted accurately," Roebuck said, remembering a training session for election workers in that year's presidential primary.

It's skepticism he said has now been building up for years, leading to the kind of election education he's doing now in an effort to instill confidence in the system.

"It's so important for us as election administrators to be transparent about what we're doing and for voters to be able to ask questions and get answers and see the process play out for themselves," Roebuck said.

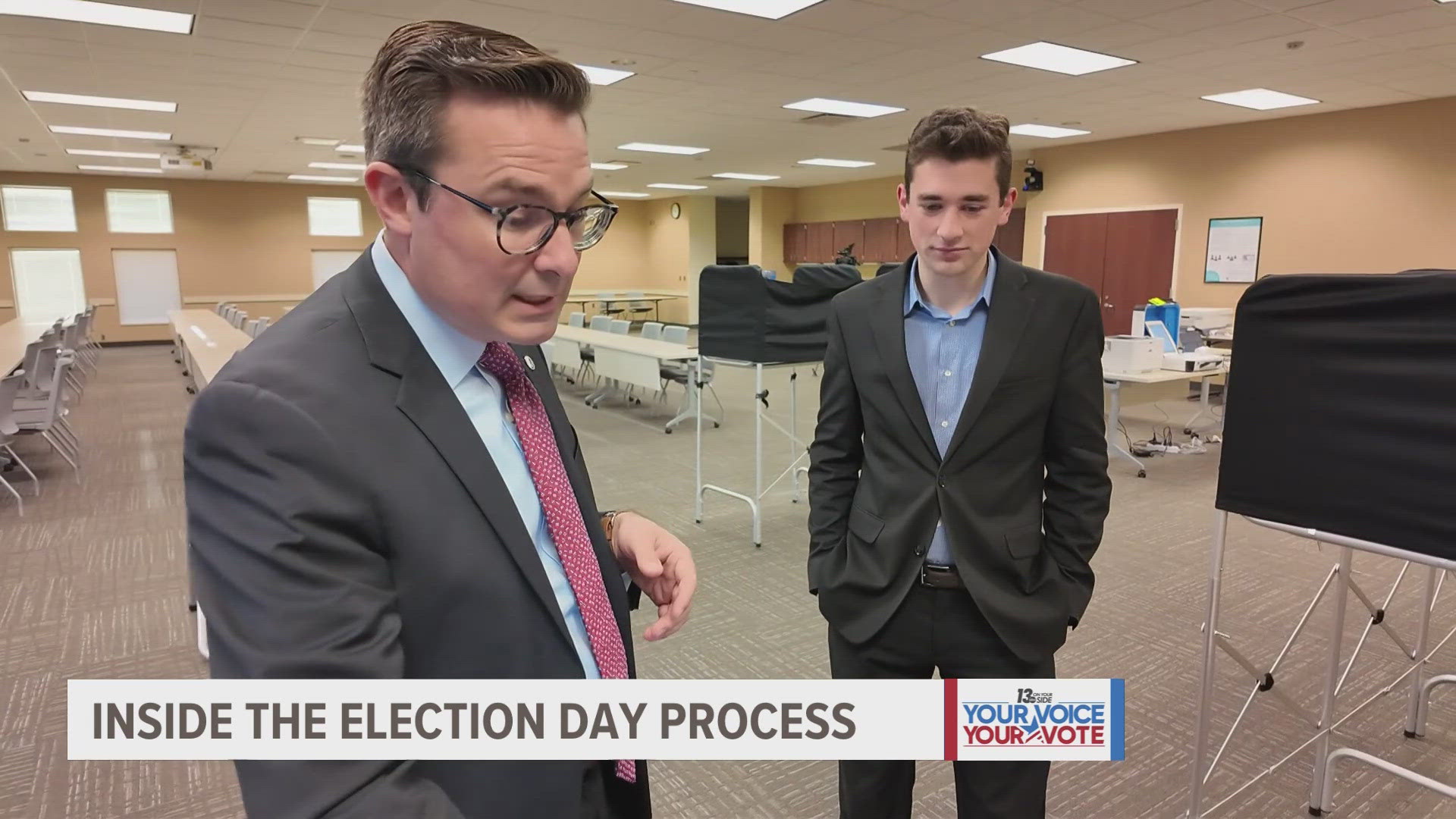

So, ahead of the election, Roebuck took 13 ON YOUR SIDE through everything a voter can expect on Election Day, including the requirement surrounding photo ID for in-person voting.

"If you don't have a photo ID, there's a process that we can go through, and you can still cast a ballot," Roebuck explained. "You can sign a legal document, essentially saying that you don't have a photo ID, that you're not in possession, but that you are registered to vote in this location."

"[If] everything else matches and checks out, we can issue you a ballot," he continued. "But for the vast majority of our voters, I'm going to check your photo ID. And what I can actually do is scan that ID and it will pre-populate in the poll book your voter information."

But for some, the concerns come from what may happen after the polls close.

Roebuck, however, has sought to broadcast a message that it's a system filled with checks and balances.

"After every voter has completed the voting process at 8 p.m. when the polls are closed, our election workers [are] in bipartisan teams," Roebuck said. "There always has to be representation from both major political parties in the precinct as our workers are working. So, they would actually close down this equipment by essentially closing the polls, which generates the total."

Three copies of the total, he said, are sent out - one to the local clerk, another to the county clerk and a third to the county board of canvassers. All three must be signed by the election workers to ensure validity.

And if that wasn't enough, a metal cage known amongst the workers as the 'tiger cage' - used to store early voting materials including ballots and tabulators during the nine-day early voting period - offered an imposing impression of security.

"This whole thing is wheeled into a secured, locked room, we're under video surveillance 24/7 in that room," Roebuck said as he wheeled out the cage that is placed under both lock and tamper-evident seal. "And the following morning, when the crew arrives to get everything out, they are checking the seal number on this cage device and making sure that nothing's been tampered with overnight."

But what about the ballots?

"[The election workers are] actually going to break a seal that is on this door here," Roebuck said, gesturing to a locked section of the tabulator set up in which the ballots were stored after being run through. "And they're going to remove the voted ballots from this box, essentially where the tabulator goes."

The ballots, he explained, are then transferred to secure containers as unofficial results, according to information given by county Elections Supervisor Katie Bard at a public event last week, are reported to the state via a secure network.

"So, the voted ballots are sealed in an approved ballot container," Roebuck said.

"In order to be approved, the ballot container has to have a sticker that is literally evidence of its being inspected by the board of county canvassers," he continued.

"There's a list that we have of approved containers," he said. "They have to inspect it for any physical, you know, ensuring that it's solid, that it has no holes in it, that it's not torn or ripped, and then these ballots are sealed in the container using a state seal."

And as to whether the machines can be tampered with, the clerk explained yet another layer of security attached to the device.

"There's a state seal that's placed on here," he said, pointing to another portion of the tabulator set up he said contained the tabulator's memory. "And that seal is placed on the equipment during the public logic and accuracy testing for the equipment, so that seal number has to be verified. It's kept in multiple places as the seal is broken, bipartisan teams are watching that process, it's recorded."

Basically, Roebuck was signaling that election workers would be able to physically see if the memory of a machine was tampered with in between official processes when the seals - reminiscent of heavy-duty zip ties - are put in place.

"Even the passwords that are required to close the polls - there would be a different set of passwords and a different authentication to clear the totals from this equipment," Roebuck said.

But even with these safeguards and more in place, concerns have swirled for years.

"I mean, I think over the past several years, we have seen a growing body of misinformation affecting our communities," Roebuck said when asked how he felt about ongoing concerns surrounding the process.

"What we want to show through our work is the transparency, the bipartisanship that is involved in this process - the complete openness to the public as far as what is happening here," he said.

"It's so important that our public sees those steps that go into the process so that they can trust the process by which they're choosing their government."