LANSING, Mich. — Karen Kobylik knew her daughter should not have a gun. She had repeatedly called the police since her daughter turned 21, pleading with them to take her firearms because of the risk she posed to herself and others.

"They said we can’t take any guns away from her because we cannot step on her Second Amendment right,” Kobylik told The Associated Press. “I was like, ‘I’m a mother telling you that this kid’s got a mental issue that is not currently being addressed.’”

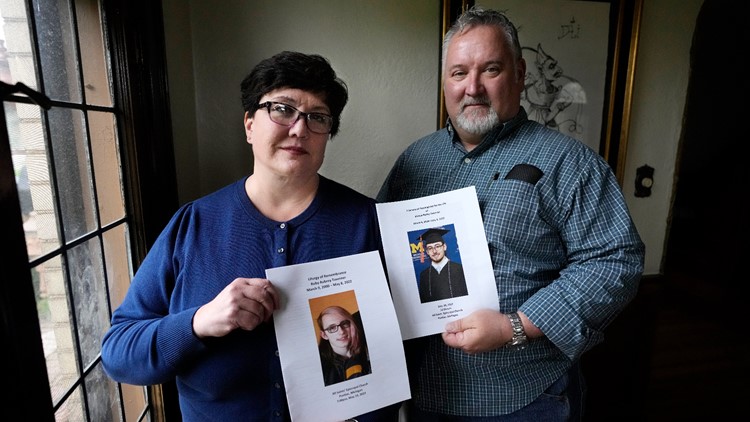

Kobylik’s daughter, Ruby Taverner, shot and killed her brother and boyfriend before taking her own life in the early morning of May 8 last year. Kobylik believes all three lives could have been saved had red flag laws, also known as extreme risk protection orders, existed in Michigan that would have allowed police to remove her daughter’s guns and prevented her from purchasing more.

Now Michigan is poised to become the 20th state — and the first in nearly three years — to pass a red flag law. It would allow family members, police, mental health professionals, roommates and former dating partners to petition a judge to remove firearms from those they believe pose an imminent threat to themselves or others.

Kobylik said her daughter had been treated for mental health problems including depression since the age of 7 but had stopped taking her medication at 18. Just days before the killings, Taverner purchased the Glock 43X used in the shooting after she had been released from a psychiatric hospital for threatening to take her own life, Kobylik said.

Taverner and her brother, Bishop, were both 22. Her boyfriend, Ray Muscat, was 24.

The red flag measure faces pushback on the local level in a state where gun-owning culture runs deep. Over half of the state’s counties have passed resolutions declaring themselves Second Amendment “sanctuaries,” opposing laws they believe infringe on gun rights. Some sheriffs have said they will have trouble enforcing something they believe is unconstitutional.

“At the end of the day, the utmost responsibility for a sheriff is to uphold the Constitution,” Van Buren County Sheriff Daniel Abbott said.

The U.S. is on a record pace for mass shootings so far this year.

Touted as the most powerful tool to stop gun violence before it happens, an Associated Press analysis in September found red flag laws are barely used in the 19 states and the District of Columbia where they exist. Firearms were removed from people 15,049 times since 2020, fewer than 10 per 100,000 adult residents, according to the analysis.

It will be the first time since New Mexico in 2020 that a state has passed a red flag law, but similar legislation is being considered elsewhere as lawmakers seek solutions.

The Minnesota House advanced a wide-ranging public safety bill last month that includes a red flag law. It remains uncertain whether the provision will make it through a conference committee.

After a Nashville school shooting in March killed six people, Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee is calling lawmakers back into session after fellow Republicans declined to take up his “temporary mental health order of protection” proposal at the end of the legislative session they concluded in April.

The Biden administration has sought to foster wider use of state red flag laws and recently approved more than $200 million to help states and the District of Columbia administer those laws and similar programs.

Red flag legislation introduced following a shooting at Michigan State University, which left three students dead and five others wounded, passed the Democratic-controlled Michigan Legislature last month and is expected to be signed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in the coming weeks. It would not take effect until next year at the earliest.

A judge would have 24 hours to decide on a temporary extreme risk protection order after a request is filed. If granted, the judge would then have 14 days to set a hearing during which the flagged person would have to prove they do not pose a significant risk. A standard order would last one year.

Lying to a court when petitioning for a protection order would be a misdemeanor punishable by up to 93 days in jail and a $500 fine.

Livingston County Sheriff Michael Murphy has already said he will not enforce the protection orders because he said they lack due process and are “ripe for abuse.” With 72 of Michigan's 83 counties voting Republican in the last presidential election, many sheriffs will have to choose between following the law or appeasing constituents.

Local officials “do have discretion as to which laws they will enforce with the resources of their office," Attorney General Dana Nessel said in a statement to the AP. She added that arguments against the orders are “based not on the law but the personal whims of what they want to support."

In the Upper Peninsula's Marquette County, Sheriff Greg Zyburt said that while he doesn’t agree with everything in the legislation, he “doesn’t pick and choose what laws to enforce.”

“It’s not my place," Zyburt said. “That’s why we have different branches of government.”

In Colorado, 37 counties that consider themselves “sanctuaries” issued just 45 surrender orders in the two years through 2021, one-fifth fewer per resident than non-sanctuary counties. New Mexico and Nevada reported only about 20 orders combined.

The laws have continued to receive widespread support from the public even with the lack of usage. An AP-NORC poll in late July found 78% of U.S. adults strongly or somewhat favor red flag laws.

Kobylik is a gun owner who considers herself a conservative. She spoke in favor of the red flag law at a Michigan Senate committee hearing in March.

“I’m not here to excuse Ruby’s actions," she said. "Far from it. What I am here to tell you is that this never had to happen.”

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the 13 ON YOUR SIDE app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@13onyourside.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter. Subscribe to our YouTube channel.