Tsunamis on the Great Lakes might sound as unlikely as major earthquakes in Detroit. But Great Lakes tsunamis are a real phenomenon that at times have proven deadly.

Some of the world's leading experts on tsunamis met in Ann Arbor last year to discuss meteotsunamis on the Great Lakes and the potential development of an early-warning system for them.

Tsunamis in our oceans are typically brought about by earthquakes — a sudden, upward thrusting of the Earth's crust rapidly displacing massive amounts of water, leading to a large, long wave that builds in intensity as it crosses the ocean.

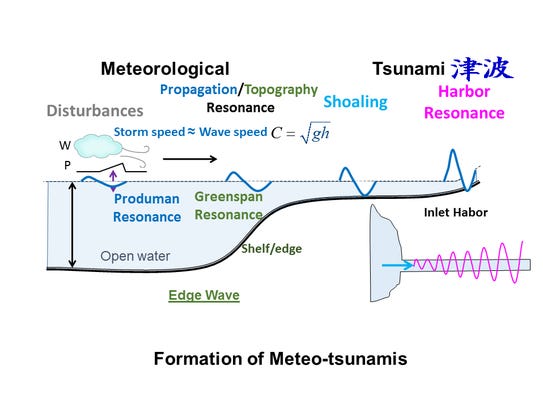

Meteotsunamis work in much the same way on the Great Lakes, but the displaced water that starts them is from sudden, very intense storms on the lakes, causing winds or barometric pressure to push down on the water.

Formation of Meteo-tsunamis (Photo: Courtesy Chin Wu, University of Wisconsin)

"I've really not heard about these things much before," said Bradley Cardinale, director of the University of Michigan's Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research, which hosted the meteotsunami discussion.

"But once I started talking to scientists, I learned these are much more common than you would expect — they occur about 106 times a year on the Great Lakes."

And they've occasionally been deadly:

- On July 4, 1929, a 20-foot wave that scientists now believe was caused by a meteotsunami crashed over holiday beach-goers on a pier in Grand Haven. Ten people were pulled out into Lake Michigan and drowned.

- On June 26, 1954, a 10-foot, meteotsunami-caused wave swept fishermen off a pier on the shores of Lake Michigan in Chicago. Seven were killed.

- On July 4, 2003, seven swimmers drowned on Lake Michigan near Sawyer in Berrien County. According to media reports at the time, the drownings occurred within a 3-hour span after a powerful thunderstorm plowed through the area that morning, producing wind gusts of 50 m.p.h.

The July 5, 1929 front page of the Detroit Free Press recounted the horror from the previous day in Grand Haven, when 10 were swept away and drowned following a huge wave. Weather experts now believe that wave was a weather-caused "meteotsunami." (Photo: Detroit Free Press)

Unlike the lake phenomenon known as seiches, in which waters flood back to their original side after being pushed by a strong weather event, like bathwater sloshing in a bathtub, meteotsunamis travel in one direction across the lake following a significant weather event. Though ocean tsunamis can be much larger and stronger, Great Lakes meteotsunamis can similarly be dangerous both as the wave is crashing on-shore, and afterward, Cardinale said.

"When a tsunami recedes, it's sort of like a vacuum," he said. "We've got seven nuclear power plants that are literally on the shore of the Great Lakes. It could potentially pull water away from intake pipes, that keeps the core of thee nuclear reactors in check."

Added Chin Wu, an environmental engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin, who is helping lead the Ann Arbor meteotsunami forum, "The energy (of the regressing wave) can sustain for 10 or 20 minutes. So you can imagine a swimmer swept far out into the lake, trying to fight it for that long."

Wu and his team examined the past 28 years' worth of meteorological records over the Great Lakes, with special attention on barometric pressure and wind speed. Then it looked for large waves on the other end, away from intense lake weather events.

"We were really shocked about how many waves we found," he said.

This graph shows how meteotsunamis can form on the Great Lakes. An intense storm pushes down on the lake at one end, displacing water. The resulting wave gains energy, size and strength as it moves across the lake, particularly as it nears shore on the other side. (Photo: Chin Wu, University of Wisconsin)

The pressure on the lake during an intense storm may be only one or two inches, Wu said. But at the other end of the lake, the propagating wave might be up to 5 feet in height, he said. That's enough to overturn boats or sweep away those on the shore, he said.

Lake Michigan appears to be most vulnerable to meteotsunamis, along with Lake Erie, in part because of general west-to-east weather patterns crossing them, Wu said.

The institute's summit meeting in Ann Arbor included experts from the National Weather Service; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Center for Tsunami Research; the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, and others.

Also up for discussion was how an early detection and warning system might work on the lakes, he said.

"We don't have any infrastructure to provide any warning to the public," Wu said.

Any system would be dealing with a much smaller time window than an ocean tsunami warning system — "we're talking about an hour or two," he said.

"Because this kind of thing is different from the traditional storm that you can predict, it needs to be a very, very rapid forecasting system," Wu said. "We're bringing in not only coastal experts, but people from computer science, who know how to deal with a big amount of data quickly."

The risk of a meteotsunami may typically be small, but "the risk is highest when people are not aware of it," Wu said.

Historical Meteo-tsunamis (Photo: Courtesy Chin Wu)

Contact Keith Matheny: 313-222-5021 or kmatheny@freepress.com. Follow on Twitter @keithmatheny.